How to Ferment Chuño

Mastering Traditional Andean Techniques

Chuño is a traditional Andean food with a rich cultural heritage, serving as a testament to the ingenuity of the Inca civilization. This freeze-dried potato product is made through a natural preservation process that harnesses the stark temperature fluctuations of the Andean highlands. The process, which has been used for over seven centuries, allows the potatoes (What wine goes well with potatoes?) to be stored for years, providing an essential source of sustenance that has carried Andean societies through periods of food scarcity.

Produced primarily in Bolivia and Peru, chuño is an integral part of the region's cuisine and remains a staple in the diet of Andean communities. Not only does it offer an excellent way to preserve the abundant potato crop in the high-altitude Andes, but its distinct texture and flavor also contributes to the region's unique gastronomy. The preparation of chuño is a multi-day process that involves exposure to the cold night air and the warm daytime sun, which alternately freezes and dehydrates the potatoes, leading to a completely natural fermentation and preservation.

Understanding the process behind chuño fermentation offers insight into the rich traditions and adaptations of Andean food preservation techniques. This has allowed the people of the high Andes to create a sustainable food system well adapted to their challenging environment. Today, chuño continues to be a beloved food for its versatility in a variety of dishes, from stews (What wine goes well with stews?) to soups, and it stands as a celebrated icon of Andean culture and Inca legacy.

Historical Context

Chuño, a freeze-dried potato product, has deep historical roots in the Andes, closely tied to the Inca Empire and the indigenous Aymara and Quechua communities. Its development and preservation over centuries signifies its cultural and dietary importance in pre-Columbian America.

Inca Origins

Chuño was first created by the indigenous people of the Andes, tracing back to the Inca civilization. This process took advantage of the high altitude's natural climate, where the temperature fluctuations between day and night are dramatic. The Incas would spread potatoes at high elevations where the night's freezing temperatures and the day's sunlight would dehydrate the potatoes, turning them into chuño after several freeze-thaw cycles. Tiwanaku, another influential pre-Columbian culture, also utilized similar methods for their sustenance.

Cultural Significance

In the cultures of the Quechua and Aymara people, chuño holds more than just a nutritional value; it is a cultural staple. This food item is intricately woven into the traditions and ceremonial practices across Andean societies. It is a crucial component of the Andean diet that has been inherited from generation to generation. Beyond Peru and Bolivia, its cultural footprint extends throughout various countries of South America where chuño continues to be a valued part of the regional cuisine.

Chuño remains a symbol of indigenous innovation and perseverance in the face of harsh environmental conditions. Its preparation is an ancient practice that reinforces the connection between the people of the Andes and their environment. The Quechua word for chuño, ch'uñu, reflects the deep linguistic roots that this food has in the region, illustrating the enduring legacy of chuño in the Andean culture.

Chuño Varieties

Chuño, a freeze-dried potato product, has been an essential food in the Andes with a history as ancient as potato cultivation itself. It comes in two main varieties, known as white chuño and black chuño, appreciated for their long shelf life and versatility in various dishes.

White Chuño

White chuño is a dehydrated potato with a pale color and a lighter taste. It is typically used as a potato starch in Peruvian and Bolivian cooking, acting as a thickening agent in sauces, desserts, and cakes. The process of making white chuño involves exposing potatoes to cold temperatures overnight and then allowing them to dry under the sun. This variety can be stored for extended periods and is commonly rehydrated for use in soups and stews.

Black Chuño

Black chuño is characterized by its darker hue and a slightly bitter flavor, made from a specific type of bitter potato. The potatoes are freeze-dried through a natural process of alternating freezing and exposure to the sun over several days, which lends the black chuño its distinct color and taste. It is equally long-lasting as white chuño, and is often incorporated into traditional Andean recipes. Black chuño offers a unique contribution to the region's culinary practices and can be found in both local markets and occasional international stores.

The Freeze-Drying Process

The freeze-drying process of chuño transforms bitter potatoes into a long-lasting food staple through dehydration and sublimation in the Andes' harsh climate.

Traditional Methods

The traditional method of producing chuño dates back centuries and is ingrained in the Andean culture. Native communities use frost-resistant varieties of potatoes, exposing them to the extreme cold temperatures and the high altitude sun. This process begins by spreading the potatoes out during the night to freeze, taking advantage of the region's sub-zero temperatures. The daytime sun then begins the sublimation process, in which the frozen water in the potatoes turns directly into vapor, effectively dehydrating them. This cycle is repeated over several days, with locals often trampling the potatoes to squeeze out any remaining moisture. The result is chuño, which can be stored at room temperature for an extended shelf life.

Modern Techniques

Although the principles remain the same, the modern freeze-drying process has advanced to become more efficient. This technique employs controlled environments where the temperature and pressure levels are carefully managed to optimize dehydration and sublimation. The potatoes are first frozen quickly, then placed in a vacuum chamber where the pressure is reduced. Here, the ice vaporizes without entering a liquid state, a process enhanced by a slight increase in temperature within the chamber. Modern freeze-drying accelerates production, ensures consistent quality, and extends the shelf life of chuños even further.

Preservation Benefits

Freeze-drying, both traditional and modern, offers significant preservation benefits. By removing moisture, chuños become inhospitable to microbial growth, allowing for a long shelf life without the use of chemical preservatives. The nutritional value is largely retained, and the lightweight, dehydrated product is easy to transport and store. Preserved chuños can last for many years, providing a reliable food source that endures beyond seasonal and environmental changes. This contributes to food security and sustains the cultural heritage within the Andes.

Nutritional Information

Chuño, an Andean freeze-dried potato product, preserves the nutritious qualities of potatoes while offering unique benefits due to its processing method.

Health Benefits

Chuño is rich in carbohydrates, providing a stable energy source. Its freeze-drying process in the high altitudes of the Andes minimizes the loss of nutrients, ensuring that important vitamins and minerals are retained. It's especially notable for a modest iron content, which is crucial for preventing anemia and supporting overall health. Additionally, chuño is low in fat and contains dietary fiber, which aids in digestion.

Comparison with Other Potatoes

When compared to regular potatoes, chuño stands out for its long shelf life and nutrient retention due to the freeze-drying process. While other potatoes might lose some of their nutritional value during cooking or lose freshness over time, chuño maintains its properties for extended periods. Regular potatoes typically have higher water content, which chuño lacks due to the freeze-drying process, making chuño a concentrated source of potato starch and nutrients.

Preparing and Cooking Chuño

Chuño, a traditional food from the Andes, undergoes a unique dehydration process that concentrates its flavors. The preparation of chuño involves a rehydration process, after which it can be incorporated into various dishes like soups, stews, sauces, and desserts.

Rehydration Process

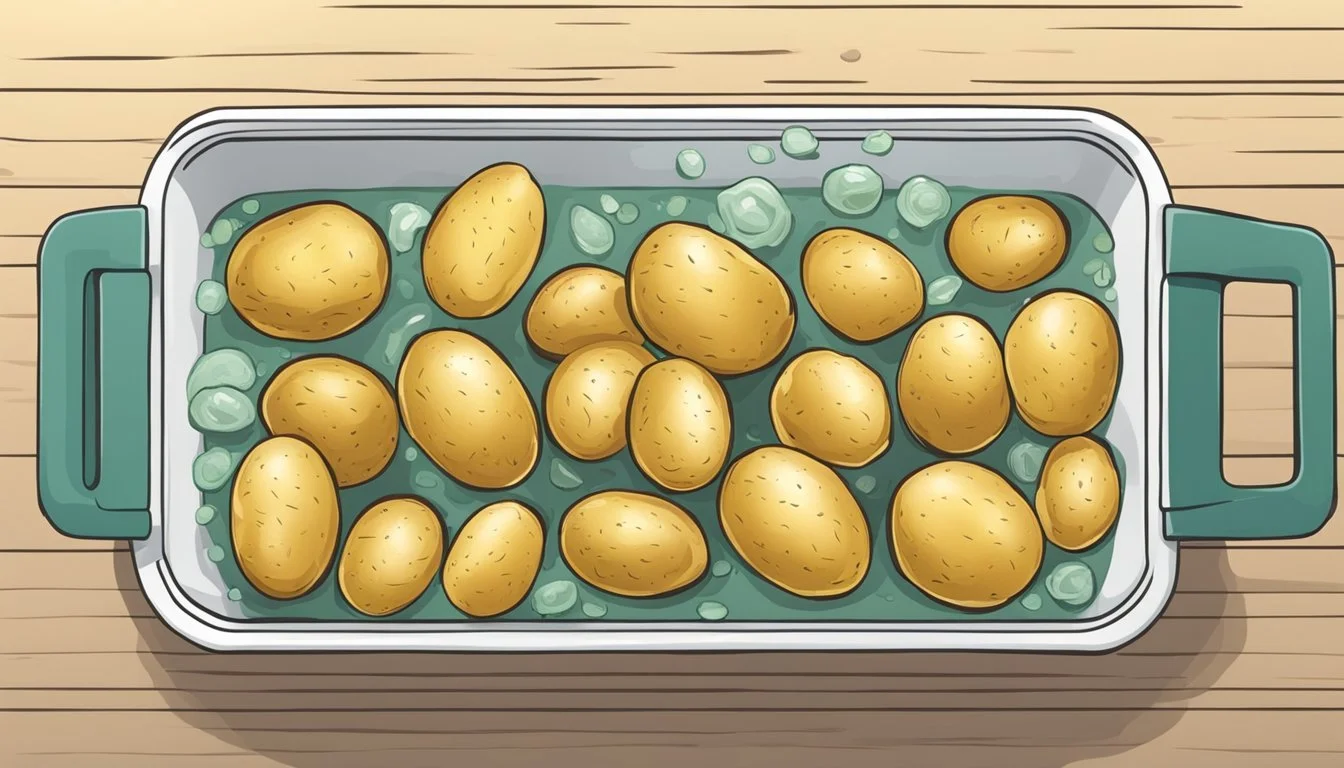

Before cooking, chuño must be rehydrated to soften its texture. This is usually done by soaking the chuño in water. The recommended steps are:

Rinse the chuño thoroughly to remove excess dirt and any bitterness.

Submerge the chuño in a bowl of cold water.

Allow the chuño to soak for 24-48 hours, changing the water a few times during the process.

Once the chuño has swelled to near its original size and is suitably soft, drain it well.

Incorporation into Dishes

Once rehydrated, chuño can be used to add substance and flavor to an array of traditional Andean dishes. Some specific applications include:

Soups and Stews: Chuño provides a hearty, earthy component. Add it to a boiling broth and let it simmer to fully infuse the chuño with the dish's flavors.

Sauces: Chuño can thicken sauces owing to its starchy composition. It should be finely mashed or blended before being whisked into the desired sauce.

Desserts: Less common, but still viable, chuño can also be used in desserts, typically after a fine grinding into a potato starch.

When incorporating chuño into culinary creations, chefs take advantage of its robust texture and the unique taste that comes from its freeze-dried origins. Whether in a rich beef stew (What wine goes well with beef stew?) or a warming chicken soup, this Andean staple adds a distinct character recognized by discerning palates aiming to experience authentic South American cuisine.

Regional Dishes Featuring Chuño

Chuño, the freeze-dried potato staple of the Andes, serves as a versatile ingredient in numerous regional dishes. It holds a significant place in traditional Andean gastronomy and now finds its way into innovative culinary creations.

Andean Soups and Stews

Chuño plays a foundational role in many hearty Andean soups and stews. These dishes are a testament to the ingenuity of Andean communities in maximizing the longevity and utility of their food resources.

Chairo: This robust stew is a blend of chuño, meat, vegetables, and local spices. It's a staple food that provides necessary warmth and nutrition in the cold altitudes of the Andes.

Jakonta: Often prepared during special festivals, jakonta is a traditional soup that combines chuño with a variety of meats and tubers, cooked slowly to absorb the flavors thoroughly.

Desserts and Confectioneries

Though chuño is commonly associated with savory dishes, it also finds its place in dessert recipes within the Andean diet.

Chuño flour is used as a starch in cakes and desserts, offering a unique texture and slight earthiness that differentiates Andean sweets from more familiar confectioneries.

Modern Fusion Cuisine

The incorporation of chuño into modern fusion cuisine illustrates its adaptability and the innovative spirit of contemporary chefs.

Inventive dishes merge traditional elements with international influences, featuring chuño in unconventional presentations that still pay homage to its Andean roots. For example, chuño might be used as a textural contrast in modernized versions of classic Andean dishes.

Through these culinary expressions, chuño remains an essential component of the Andean food identity. It travels from archaeological sites of ancient preparation methods to the cutting-edge kitchens of today's fusion restaurants, showcasing its timelessness and adaptability.

Storage and Shelf Life

When it comes to storing chuño, the traditional Andean freeze-dried potato, its long shelf life is one of its most significant advantages. Dehydrated chuño does not require refrigeration and can be kept in a cool, dry place away from direct sunlight. The optimal storage conditions will ensure that chuño retains its quality and nutritional value.

A proper storage environment should maintain low humidity to prevent moisture absorption, which can interfere with the longevity of the product. If chuño absorbs moisture, it may lead to spoilage or mold. Therefore, it is essential to keep it in airtight containers or sealed bags.

The shelf life of chuño can extend from a few months to several years, although it will vary depending on storage conditions. The lack of moisture within the product deters bacterial growth and spoilage, which contributes to its impressively long shelf life. This characteristic makes chuño an excellent choice for long-term food storage, and an asset in situations where fresh food is scarce or unavailable.

Here is a quick reference table for chuño storage:

Factor: Temperature

Recommendation: Cool and stable

Factor: Humidity

Recommendation: Low, avoid moisture exposure

Factor: Container

Recommendation: Airtight, to prevent spoilage

Factor: Shelf Life

Recommendation: Several months to years

Factor: Light

Recommendation: Away from direct sunlight

In summary, chuño should be stored in conditions that are devoid of moisture and large temperature fluctuations. By following these guidelines, one can maximize the shelf life of this Andean staple, ensuring that these nutritious potatoes can be enjoyed well into the future.

Chuño in Modern Culture

Chuño remains a cultural emblem of the Andes, closely associated with the traditions of the Inca and Aymara peoples. In contemporary times, this ancient food staple is experiencing global recognition for its historical significance and unique processing technique.

Continued Tradition in Andean Communities

In the highlands of the Andes Mountains, Andean communities continue the practice of making chuño as they have for centuries. This method, which freezes and dries small potatoes, is mainly sustained by the indigenous Aymara and Quechua peoples. These communities still utilize the nighttime frost and daytime sun of the Andean plateau to naturally process the potatoes, adhering closely to the techniques developed by their ancestors. This cultural practice preserves not only the potatoes but also a piece of their heritage, passing it down through generations as both a sustainable food source and a way of life.

Global Recognition

Chuño has stepped onto the global stage as an atlas obscura within the culinary world. It has become a topic of interest for those looking to explore ancient Incan methods of food preservation. The attention chuño has garnered is partly due to its long shelf-life and nutritional value, traits that make it comparable to modern astronaut food. This freeze-dried potato has been embraced by chefs, food enthusiasts, and cultural scholars alike, intrigued by its integration into modern cuisine while respecting its ancient roots. Global recognition of chuño highlights the marvel of Incan innovation and the enduring legacy of Andean culture.

Conclusion

Chuño represents not just a food source but a vital cultural artifact that has enabled the people of the Andes to thrive in harsh environments. This method of preservation has stood the test of time, reflecting a deep understanding of nature and the ability to adapt traditional practices to modern needs.

The success of chuño lies in its simplicity and effectiveness. By utilizing the natural freeze-thaw cycle of the high Andes, inhabitants have developed a sophisticated method to extend the life of their potato crops. This nutritious alternative to fresh potatoes can be stored for long periods, providing an essential food reserve during times of scarcity.

In creating chuño, the Andean people employ a process that aligns with their environment and traditions. This approach is a testament to their resourcefulness and ingenuity—a true blend of culture and survival.

For those interested in exploring Andean cuisine or food preservation, chuño offers a unique insight into a time-honored technique. It serves as a reminder of the resilience of traditional food systems and their ongoing relevance in a dynamic world.