How to Ferment Salami

Mastering Fermented Sausage at Home

Salami, a type of fermented sausage, is a staple of charcuterie (What wine goes well with charcuterie?) that owes its unique flavors and preservation to the process of fermentation. Fermentation is a controlled microbial growth and enzymatic activity that develops the salami's texture and tangy taste. This age-old technique not only enhances the organoleptic properties of the sausage but also contributes to food safety. By encouraging the growth of beneficial bacteria, the pH of the sausage is lowered, creating an environment that is inhospitable to harmful pathogens.

The key to successful salami fermentation is precision. It begins with preparing a mixture of ground meat, typically pork, combined with a specific blend of salt, spices, and curing agents such as sodium nitrite or nitrate. The use of a starter culture, comprising select strains of bacteria, is a crucial development in modern methods. These cultures are rehydrated and added to the meat mix, ensuring consistent and reliable fermentation. After stuffing into casings, the salami is left to ferment at controlled temperatures and humidity levels to cultivate the desired acidic environment.

Cured sausages like salami are categorized into semi-dry and dry-types based on their moisture content after the curing process. This distinction affects aspects of storage and consumption while the fundamental principles of fermentation remain the same. The overarching goal is to achieve a harmonious balance between safety, flavor, and shelf stability. As a result, precise handling and an understanding of the fermentation process are essential to crafting high-quality salami.

Understanding Fermentation

Fermentation in salami making is essential for developing flavor, preventing spoilage, and ensuring safety. It involves complex biochemical processes that require precision and understanding.

Principles of Fermentation

Fermentation is the metabolic process where lactic acid bacteria convert carbohydrates (such as the sugars in meat) into lactic acid. This acidification is crucial as it lowers the pH of the salami, creating an environment that is hostile to harmful bacteria and permits the growth of beneficial bacteria. The decrease in pH is a key marker for successful salami fermentation; typically, a final pH below 5.3 is desired for both safety and flavor.

There are two main types of fermentation in salami making: natural fermentation and fermentation using a starter culture. Natural fermentation relies on bacteria that are naturally present in the meat and the environment. However, it is less predictable and can lead to inconsistent results.

Role of Starter Cultures

A starter culture is a preparation of specific microorganisms, usually strains of lactic acid bacteria, which is added to the salami mix to kickstart the fermentation process. The use of a starter culture is the most consistent way to ferment dry cured salami because it provides control over the fermentation process, ensuring reliable acid production, flavor development, and safety.

The starter culture is typically kept frozen and rehydrated before being added to ensure its effectiveness. During fermentation, the temperature and air humidity are controlled to support the growth of the starter culture. This regulated environment allows the bacteria in the culture to rapidly produce lactic acid, thereby ensuring a drop in pH to the safe and desired levels.

Selecting Ingredients

The quality of ingredients in salami crafting is pivotal; they define the flavor, texture, and safety of the final product. Precise selection of meats and adjuncts determines the fermented sausage's distinctiveness.

Choosing Your Meat

Meats: The cornerstone of salami is the meat used, predominantly pork and beef. One should opt for high-quality, fresh cuts; the meat should not only taste good but also have the right fat content.

Pork: A popular choice due to its rich flavor and fat content.

Primary cuts:

Shoulder: A balanced mix of fat and meat.

Belly: Higher fat, adding succulence.

Beef: Adds depth to the flavor profile.

Commonly used cuts:

Chuck: Leans towards a meatier texture.

Brisket: A tougher cut with flavorful fat.

Fat: Crucial for texture and taste, it also aids in fermentation. Back fat from pork is a traditional choice, providing a firm texture and creaminess.

Recommended fat proportion: 20-30% of the meat mixture.

Pork fat, known for its pure, white appearance and subtle taste, is preferred.

Spices and Flavoring

Spices and flavoring agents are not merely add-ons; they are integral to the character of the salami.

Essential Spices:

Salt: Essential for curing and flavor; about 2.5-3% of the meat weight.

Pepper: Ground black or white pepper are common for heat and pungency.

Garlic (What wine goes well with garlic?): Often used for its pungency; fresh or in powder form.

Flavor Enhancers:

Wine or vinegar: For acidity and complexity.

Herbs: Such as thyme or fennel seeds, for aromatic notes.

Each spice should be measured carefully to maintain balance and ensure the safety of the fermentation process. The recipe should be precise and consistent to produce a predictable and desired outcome every time.

Preparation for Salami Making

Before embarking on the journey of salami making, one must ensure that all ingredients and equipment are prepared with precision. It's about achieving the correct balance of flavor, safety, and texture. Proper grinding, mixing, and casing are pivotal in this initial phase.

Grinding and Mixing

The first step in salami preparation is to grind the meat and fat. The selection of meat is typically a combination of lean pork with high-quality fat. One should grind the meat using a medium-sized plate around 6mm. This process ensures that the fat and meat are evenly incorporated while maintaining a good texture. After grinding, the mixture should be chilled to below 34°F (1.1°C) to maintain the integrity of the protein structure.

The mixing of the ground meat follows, requiring precision with the addition of salt, sugar, or dextrose, and any other preferred seasonings. This is also the stage to add a starter culture, if using, which will bring about controlled fermentation. Stir the mixture until the ingredients are thoroughly distributed, and a sticky texture is achieved, indicating that the proteins have been well extracted.

Stuffing and Shaping

Once mixed, the salami meat needs to be stuffed into casings, which give the salami its shape and contribute to the curing process. Selecting the right type of casing is crucial, as it affects the texture and drying of the salami. Natural casings are commonly preferred for their ability to breathe and contribute to the distinctive fermented flavor.

After stuffing, the salami should be shaped with care, eliminating air pockets that can spoil the product. The sausages are then left to ferment at a specific temperature, usually between 68°F and 86°F (20°C to 30°C), and a controlled humidity level. This environment stimulates the beneficial bacteria to grow, which lowers the pH of the meat, developing the unique tangy taste and securing safe preservation.

Curing and Drying Process

The curing and drying process is a crucial phase in salami production, ensuring safety and flavor development. Proper management of humidity and temperature is key to achieving the desired moisture level and shelf life of the product.

Curing Methods

The salami is treated with a cure mix typically containing salt, nitrites, and sometimes sugars, which serves to preserve the meat and prepare it for the drying phase. Curing can be done either through rubbing the mix onto the meat or by immersing the meat in a curing solution. During this stage, it is imperative to maintain a controlled environment to prevent the growth of harmful bacteria and to start the moisture reduction process.

Drying Phases

The drying process begins once the meat has been adequately cured. Salami is usually air dried, with specific humidity levels crucial for proper drying. The aim is to reduce the salami's moisture content evenly, preventing the exterior from becoming too dry and the interior from remaining too moist. Maintaining a relative humidity of around 85% initially, which will then be lowered gradually, helps ensure even drying. Over time, the humidity is reduced to balance the drying process and stabilize the salami, thereby enhancing its shelf life and taste profile.

Safety and Quality Control

In the process of fermenting salami, maintaining safety and ensuring high-quality standards are critical. Specific parameters such as water activity (aw) and pH levels are monitored and controlled to inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria and ensure the final product is safe for consumption.

Controlling Water Activity

Water activity (aw) is a measure of the available water in a product for microbial growth. In the context of salami, keeping the aw low is crucial to prevent the proliferation of bacteria like Clostridium botulinum, which can cause botulism. The target aw value to ensure safety is generally below 0.85. Methods to control water activity include:

Curing with Salt: Salami is cured with salt, which binds to the water, reducing aw and enhancing flavor.

Drying: Lengthy drying periods further reduce aw, stabilizing the product.

Use of Nitrates and Nitrite: Small amounts of these compounds can be used to cure the meat and decrease aw, while also serving to hinder microbial growth and add a characteristic flavor.

Monitoring pH Levels

Monitoring and adjusting the pH levels during salami fermentation is essential to develop the desired flavors and textures, while simultaneously ensuring the suppression of harmful microorganisms. The process generally aims to achieve a pH of 5.2 or lower for fast fermentation, while slow-fermented salami may have a stable pH of up to 5.5 due to prolonged drying times. Key considerations include:

Starter Cultures: Cultures, such as Lactobacillus, are added to encourage the fermentation process, producing lactic acid and resulting in a lower pH.

pH Testing: Regular testing throughout the fermentation process ensures that the pH is dropping as expected to create an unfavorable environment for pathogens.

Control of both water activity and pH levels are non-negotiable measures in the salami fermentation process to guarantee a product that is not only flavorful but also adheres to food safety regulations.

Advanced Techniques

In the process of fermenting salami, particular advanced techniques are pivotal for achieving desired flavor profiles and textures. Expertise in controlling the fermentation environment and ingredient ratios is necessary to enhance the complexity of the salami.

Flavor Maturation

Flavor maturation in fermented salami hinges upon the precise regulation of temperature and humidity. These conditions allow beneficial bacteria to thrive and produce a tangy flavor characteristic of high-quality dry sausages. Starter cultures should be selected based on the specific flavor profile desired; some cultures will produce a sharper tang, while others may contribute to a more subdued acidity. For instance:

Lactobacillus sausages: A culture that promotes lactic acid will create the classic tangy salami flavor.

Staphylococcus sausages: A culture that produces slight acidity and enhances color.

Proper control over fermentation stage parameters is crucial since it governs the development of the salami's flavor. The fermentation temperature usually ranges from:

68°F (20°C) for a faster, more pronounced acidic profile,

down to 60°F (15°C) for a slower fermentation, resulting in a milder flavor.

Creating Different Textures

Texture is a fundamental characteristic of fermented sausages, affected by factors such as grinding, stuffing, and drying methods. Coarser grinds will generally lead to a more rustic and dense mouthfeel, while finer grinds will create a smooth, homogenous texture. The level of compaction during stuffing also influences the final texture:

Tightly stuffed sausages will have less air and moisture content, leading to a denser product.

Loosely stuffed sausages will be slightly softer and retain more moisture.

The drying process, crucial for texture formation, is stratified by the type of sausage:

Dry-cured sausages are aged longer and have a firmer texture.

Semi-dry sausages are often partially dried then smoked or cooked, producing a softer, yet firm texture.

The duration and conditions during the drying phase result in either a supple or a hard chewiness. Precision in humidity control—maintaining around 75%-85% RH—and a steady temperature within the 53°F (12°C) to 59°F (15°C) range promote an environment for the optimal texture development in dry sausages.

Regional Variations

Salami, a form of fermented sausage, exhibits distinct characteristics and preparation methods that are deeply influenced by regional culinary traditions. These variations often reflect local preferences and historical techniques.

European Salami Styles

In Europe, each country presents its unique twist on salami, with Italy and Spain being prominent for their varieties. Italy is renowned for its salami, with numerous regional styles like the slow-fermented, air-dried Soppressata and the garlic-rich Salami di Felino. The crafting process often involves a careful blend of pork, beef, and regional spices, cured over extended periods to develop complex flavors.

Spain is famous for chorizo, a hallmark fast-fermented sausage, characterized by its bright red color and the bold use of pimentón (smoked paprika). Chorizo comes in two main varieties: fresh, which requires cooking, and cured, which is ready to eat and has undergone a fermentation process.

United States and Other Regions

The United States has a rich tradition of sausage-making, integrating influences from European immigrants with local ingredients. The most familiar variety perhaps is the summer sausage, a semi-dry sausage largely derived from European styles, adapted to American tastes, and often consumed during picnics and as part of holiday feasts.

In addition to these traditional styles, the U.S. produces several unique fermented sausages such as Bologna, which is a semi-dry variant reminiscent of Italian mortadella, but with a texture and flavor profile suited to American palates. Innovations often lead to the production of both fast-fermented varieties that are available quickly, and slow-fermented ones that are cured over longer periods to achieve depth of flavor.

Serving and Pairing

When serving fermented salami, one should consider the complementing flavors and textures that enhance the overall experience. Proper pairing with accompaniments like cheese, bread, and beverages can elevate the distinct taste of salami.

Charcuterie Boards

Fermented salami is a star player on any charcuterie board. It should be sliced thinly to fully appreciate its complex flavor profile. To curate a well-balanced board, include a variety of textures and flavors:

Cheese: Offer a range from sharp, aged cheddar to creamy brie.

Bread: Sliced baguette or artisan crackers provide a crunchy base.

Fruit: Fresh grapes or figs can add a hint of sweetness.

Vegetables: Pickled vegetables (What wine goes well with pickled vegetables?) or olives bring acidity to balance the rich salami.

Mustard: A small bowl of grainy mustard adds a tangy spice.

Pairings with Other Foods

Salami pairs well with food and drinks that can cut through its fattiness and complement its tanginess.

Bread: A crusty loaf of bread, like ciabatta, makes an ideal vessel for salami.

Beer: A hoppy IPA or a crisp lager complements the saltiness of the salami.

By considering these pairings, one ensures each bite of fermented salami is as delectable as intended.

Storage and Preservation

Proper storage is essential for maintaining the quality and safety of fermented salami. The process involves managing temperature and humidity to prevent spoilage and ensure the salami matures perfectly.

Short-Term Storage Challenges

During the short-term storage of salami, the primary concern is preventing the onset of undesirable mold growth while allowing beneficial mold and yeast to flourish. It is recommended to store salami in a refrigerator at temperatures between 34°F (1°C) and 40°F (4°C). This temperature range slows down any harmful bacterial activity and preserves the salami for a few weeks up to a couple of months. The environment should be slightly humid to prevent the salami from drying out too quickly, but not so humid as to promote the growth of harmful bacteria.

Key Points:

Optimal Temperature: 34°F - 40°F

Humidity: Moderate to prevent drying out

Long-Term Preservation

For long-term preservation, cured sausages like salami and pepperoni are often aged in a controlled environment that mimics traditional curing rooms. After the fermentation process, the salamis must be hung in an area where temperature and humidity can be closely monitored. A typical temperature range for drying and aging salami is 50°F (10°C) to 60°F (15.6°C), with a humidity level of 60% to 80%.

It's also crucial to ensure that salami is adequately dried before it is stored for the long term. Dry cured sausages should have a firm texture and should not feel soft or squishy. They can be wrapped in paper or cloth to allow ventilation and then placed in a cool, dry place such as a cellar. Regular inspections are necessary to check for any signs of spoilage.

Key Strategies:

Drying Temperature: 50°F - 60°F

Humidity for Aging: 60% - 80%

Inspection: Regular checks for spoilage

Health and Nutrition Considerations

When enjoying fermented salami, it's important to consider both health benefits and risks. This section will explore the nutritional impacts of consuming fermented sausage and discuss the balance necessary for a healthy diet.

Understanding Risks

Fermented sausages, such as salami, typically contain preservatives like sodium nitrate and sodium nitrite. Although these compounds help prevent the growth of harmful bacteria, they can transform into potentially carcinogenic compounds called nitrosamines when exposed to high heat and acidic conditions. The presence of nitrates, which occur naturally in some vegetables, poses a similar risk when used in meat curing.

Sodium Content:

Salami is also known for its high sodium content, which is crucial for the fermentation and curing process. However, high sodium intake can be associated with increased blood pressure and the risk of heart disease.

Balancing Consumption

Moderation is key when incorporating fermented sausages into one's diet. While they can be part of a balanced diet, it's vital to limit the portion sizes and frequency of consumption due to the potential health risks associated with their ingredients.

Dietary Fiber: Some manufacturers are adding dietary fiber to salami to potentially offset some risks and provide functional health benefits, such as prebiotic effects, which support the growth of beneficial gut bacteria.

Consumers should be mindful of these factors to make informed choices about fermented sausage in their diets.

Culinary Traditions and Innovation

In the realm of fermented foods, salami stands as a testament to a rich history and an evolving culinary craft. This section dives into the age-old techniques and modern twists that define salami making, from artisanal practices to industrial innovation.

Historic Salami Making

Historically, salami preparation involved a meticulous process, deeply rooted in local culinary traditions. Traditional salami making started with the selection of meats—often a mix of ground pork, lean muscle, and quality back fat. Adding natural spices and salts followed this to enhance flavor and aid in preservation. The key to fermentation was the introduction of beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus plantarum, Staphylococcus, Pediococcus, and Kocuria. These bacteria initiated the fermentation, breaking down sugars to produce lactic acid, which lowered the pH and provided salami with its distinct tangy taste.

Fermentation occurred in a controlled environment, where temperature and humidity were carefully monitored to prevent the growth of harmful pathogens like Staph. aureus. This step could take place in traditional settings such as a cellar or a smokehouse, where the sausages were hung to ferment at temperatures close to body warmth. Post-fermentation, salami was dried, a phase crucial for developing the final texture and flavor.

Modern Adaptations and Trends

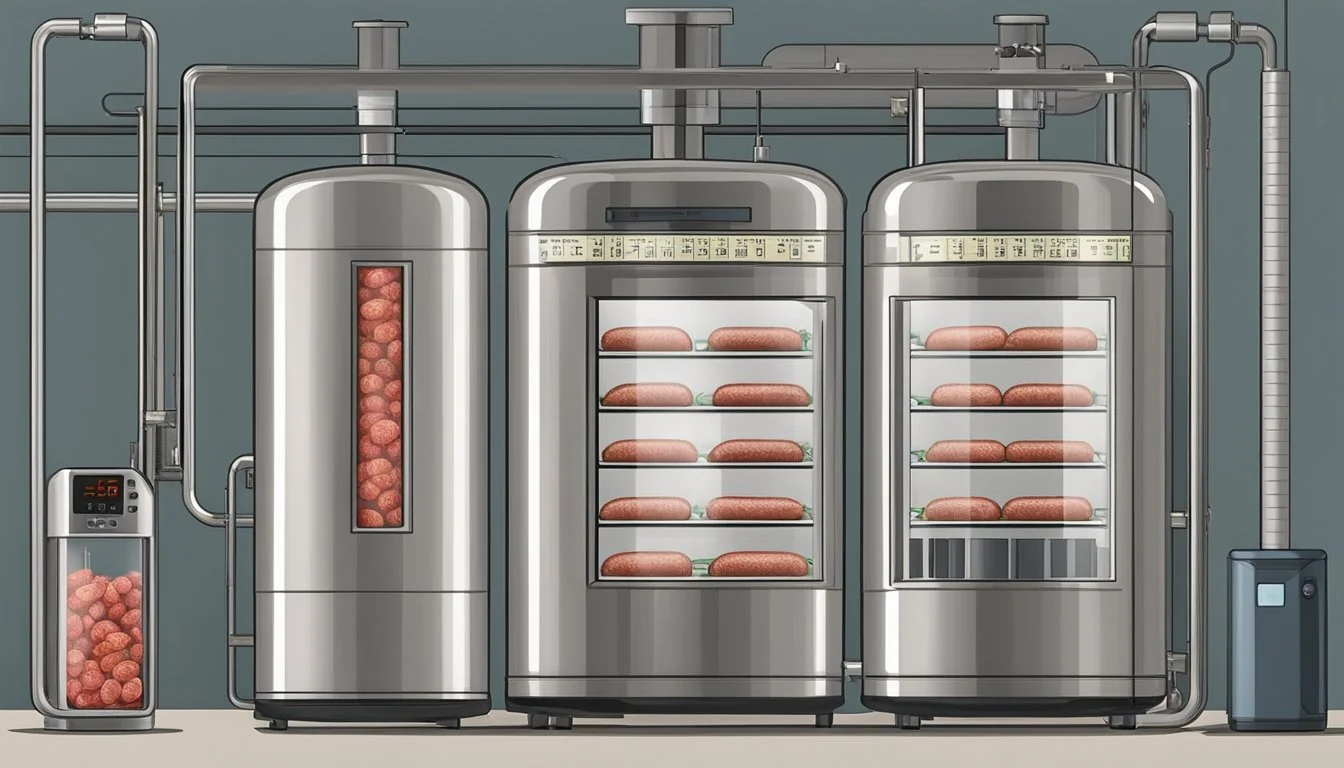

The modern take on salami making includes innovative approaches that infuse new flavors and techniques while still respecting the foundational processes. Innovation in salami production addresses both consumer preferences and safety. With advancements in food science, synthetic starter cultures can now be used to kickstart fermentation more reliably, ensuring consistent acidity and mitigating risks of pathogenic bacteria. Moreover, today's methods have expanded the scope of raw materials, leading to a broader variety of salami types, with some even using non-traditional meats or incorporating global spices and wine.

Temperature-controlled fermentation chambers and automated systems have replaced the old cellar and smokehouse environments, streamlining production while adhering to traditional fermentation principles. Additionally, modern curing chambers utilize precise humidity and airflow control, allowing for uniform drying and maturation of salami. These technological advancements have paved the way for a surge in artisanal and craft salami producers who are exploring the limits of flavor and texture, thus marrying tradition with contemporary tastes.