Stocking Rate Massachusetts

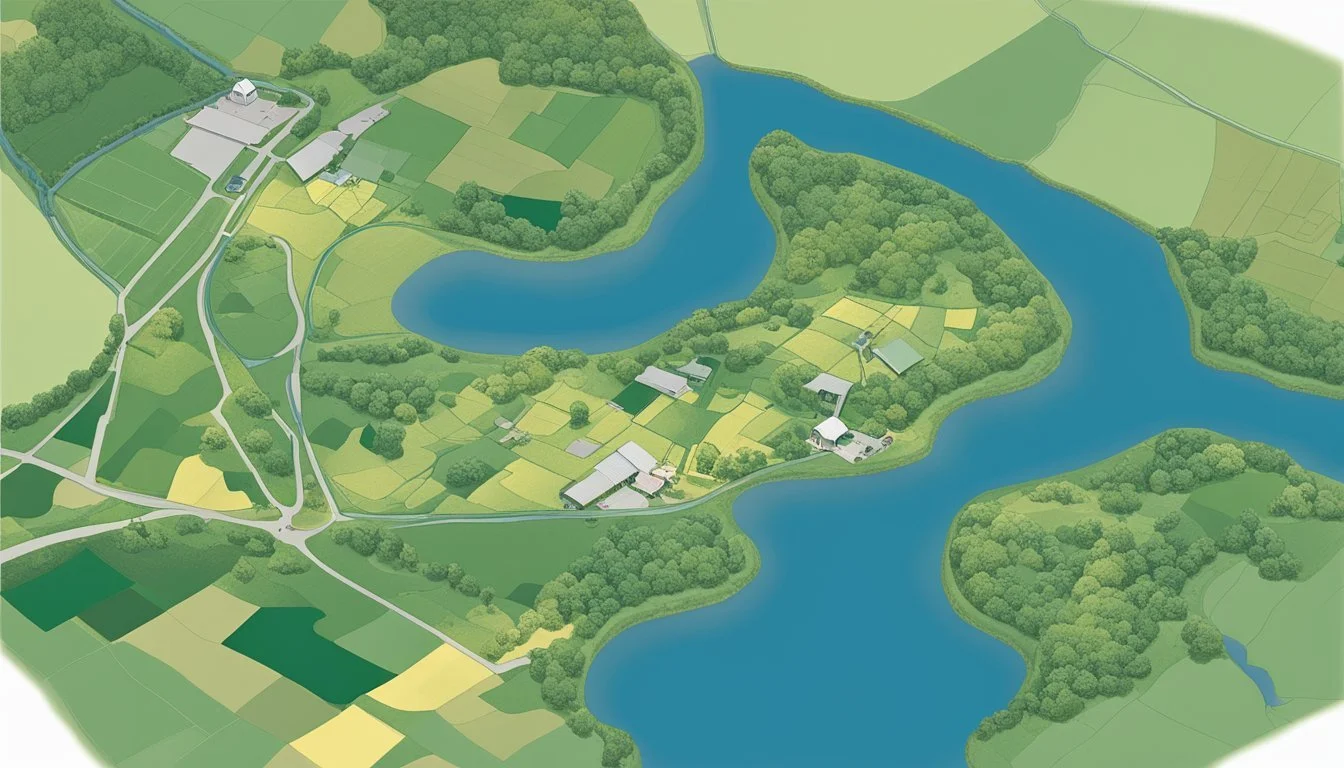

Determining Your Land's Cow Capacity

Determining the appropriate stocking rate is crucial for sustainable livestock farming in Massachusetts. Stocking rate refers to the number of animals per unit area of land that can be supported without causing environmental degradation, and without the need for supplemental feed. It is a balance between the forage availability, which is influenced by soil quality, water availability, and plant species mix, and the nutritional demands of the dairy cattle.

In Massachusetts, varied climatic and soil conditions can significantly impact pasture productivity. Consequently, there is no one-size-fits-all answer to how many cows a property can support per acre. Farmers must consider several factors, including the weight of the cows, the production stage of the livestock, and the length of the grazing season, which in turn affects forage demand and supply.

The concept of Animal Unit Months (AUM) is often used to standardize forage demand. One AUM represents the amount of forage a 1,200 lb cow without a calf would consume in one month, approximately 780 pounds of air-dried forage. Adjustments to this figure are necessary based on livestock type and specific production stages, which allows farmers to estimate the number of cows their property can support to maintain a balance between forage demand and supply.

Understanding Stocking Rate

When determining how many cows a property in Massachusetts can support, it is essential to consider the stocking rate. This rate is strongly influenced by factors such as the type and quality of forage available, the health of the pasture, and the fertility of the soil.

Defining Stocking Rate and Animal Units

Stocking rate is the ratio of animals to the pasture land available to them over a specific period and is typically expressed as animal units per acre. An animal unit (AU) represents a standardised measurement that equates the forage demand of different livestock types to that of a 1,000-pound cow. For instance, a 1,200-pound cow might be considered as 1.2 AU.

Forage Production Basics

Forage production in Massachusetts pastures hinges on the growth of grasses and legumes, which form the primary diet for grazing cattle. Adequate forage production ensures that each animal unit receives enough to meet nutritional demands without overgrazing. The production is influenced by rainfall, temperature, and the specific mix of plant species present.

Pasture Quality Assessment

Pasture quality refers to the nutritional value and palatability of the plants available to livestock. A high-quality pasture will have a variety of plant species, including preferred grasses and legumes, which contribute to both the diet variety and the overall health of the pasture ecosystem.

Soil Health and Fertility

The fertility of the soil plays a pivotal role in forage production and, consequently, the stocking rate. Properly managed soil with high fertility supports vigorous forage growth, whereas depleted soils can reduce forage yield and quality, thus affecting the stocking rate negatively. Regular soil testing can guide amendments to maintain optimal fertility levels.

Calculating Stocking Rate for Massachusetts

In Massachusetts, the stocking rate—the number of cows an acre of pasture can support—is influenced by multiple factors including the carrying capacity of the land and the regional climate conditions.

Determining Animal Unit Months/Acre

An Animal Unit Month (AUM) represents the amount of forage required to sustain one animal unit, typically a cow of about 1,000 pounds, for one month. To calculate the stocking rate in Massachusetts, one must first determine the AUMs per acre the property can support. This requires an accurate assessment of the annual forage production on the property. For instance, a rough estimate could be 1.5 AUMs per acre, depending on forage availability.

Considering Climate and Precipitation Factors

The climate in Massachusetts, classified as humid continental, has a significant impact on forage growth and subsequently on stocking density. The precipitation patterns, both annual and seasonal, influence forage production with pasture recovery typically taking from 2 to 6 weeks. Stocking rates must be adjusted to reflect these conditions to avoid overgrazing and protect the long-term health of pastures.

Assessing Seasonal Forage Variation

The grazing season in Massachusetts varies, with peak forage growth occurring in late spring through early fall. Seasonal forage variation must be accounted for when calculating stocking rates. During peak growing periods, pastures may support a higher stocking density, while slower growth periods necessitate a reduced density to allow for pasture recovery and prevent overuse.

Management Practices Impact on Stocking Rate

Effective management practices are crucial to maintaining sustainable stocking rates. Rotational grazing, proper irrigation, and soil fertility management can enhance forage production, which may lead to an increase in the sustainable number of cows per acre. Each acre of pasture should support grazing pressure that aligns with the health of the ecosystem and the needs of the livestock while considering the producers' management capacity.

Calculating the correct stocking rate in Massachusetts involves careful consideration of the unique regional factors that influence a property's grazing capability. Implementing adaptive management practices can optimize the carrying capacity and overall productivity of the land.

Grazing Management Strategies

Effective grazing management strategies are essential for maximizing pasture productivity and supporting a healthy livestock population. This section delves into the nuances of rotational grazing, continuous and intensive grazing techniques, and underscores the importance of managing grazing for optimal regrowth.

Introduction to Rotational Grazing

Rotational grazing involves dividing a pasture into several paddocks and moving livestock between them systematically. This approach allows forage in resting paddocks time to recover, encourages uniform grazing, and can improve pasture health and yield. Typically, a paddock should have a rest period of 20-30 days to promote adequate regrowth before being grazed again.

Continuous Grazing vs. Intensive Grazing

Continuous grazing is where cattle have unrestricted access to a pasture for an extended period. It can lead to uneven use of pastures, with some areas overgrazed and others underutilized. In contrast, intensive grazing, often synonymous with rotational grazing but with shorter grazing periods and longer rest periods, is more labor-intensive but can support higher stocking rates and improve pasture regrowth and quality.

Grazing Efficiency and Regrowth

Maximizing grazing efficiency means ensuring that cows consume a high proportion of the available forage without wasting it or causing damage that impedes regrowth. Efficient grazing practices help maintain a balance between forage consumption and growth, leading to sustained pasture productivity. Monitoring grass height and pasture conditions is crucial for timely rotations and achieving optimal grazing outcomes.

Livestock Considerations

Determining the appropriate number of cows per acre in Massachusetts involves understanding livestock nuances, their forage needs, and nutrition management.

Impact of Livestock Type and Breed

Different types of livestock have varied forage demands. Dairy cows, for instance, often require more intensive grazing management compared to beef breeds. The breed also affects stocking rates as some, like the Jersey dairy cow, might have lower forage needs than larger Holstein breeds.

Dairy Breeds: High production dairy breeds need more forage per unit.

Beef Breeds: Often more extensive and require less intensive management.

Forage Demand and Consumption Rates

Forage demand is directly linked to animal weight and type. A general rule states an Animal Unit (AU) represents a 1000-pound cow, with a 1400-pound cow being 1.4 AUs. Forage consumption rates are then based on these AUs, and grazing season length determines annual forage needs.

Cows per Acre: Influenced by the forage availability and the animal's weight.

Forage Consumption: Average dairy cow may consume around 3% of body weight in dry matter daily.

Supplemental Feeding and Nutrition

Supplemental feeding may be necessary when forage quality or quantity is insufficient, particularly during the winter months or drought conditions. This is to ensure livestock maintain performance and health.

Supplemental Feed: Includes hay, silage, or grain to fulfill nutrition deficits.

Nutrition: Proper balance of carbohydrates, proteins, and minerals is vital for livestock wellbeing.

In Massachusetts, meticulous planning and management are key to a successful stocking rate that supports the health and productivity of dairy and beef livestock.

Avoiding Overgrazing and Pasture Degradation

The sustainability of a pasture is closely tied to stocking rates and grazing management practices. Proper understanding and application of these practices are necessary to maintain soil health, forage quality, and ecosystem balance.

Identifying Signs of Overgrazing

Overgrazing occurs when plants are exposed to intensive grazing for extended periods without sufficient recovery time, leading to a decline in pasture productivity. Here are signs to watch for:

Short and sparse plant growth: Consistently grazed plants may not reach their normal height.

Bare soil and soil compaction: Increased soil exposure and compaction reduce water infiltration and root growth.

Increase in undesirable plants: Overgrazed pastures often become overrun with weeds less palatable to livestock.

Effects of Overstocking on Soil and Plant Health

Overstocking pastures exceed the land's carrying capacity, leading to numerous negative consequences, including:

Soil degradation: Soil compaction impedes root development and decreases soil aeration.

Reduced forage quality: Overgrazed forage often lacks in nutritional value, affecting livestock health.

Loss of desirable plant species: Intensive grazing pressure can lead to the dominance of less productive plant species.

Restoration Strategies for Degraded Pastures

To restore a degraded pasture, land managers should employ the following strategies:

Implement rotational grazing: Divide pastures into smaller areas to manage forage utilization and allow for plant recovery.

Adjust stocking rates: Use Animal Units (AU) to align the number of cows with the pasture's capacity to maintain forage health.

Re-seed with resilient plant species: Introduce plant species that are better suited to withstand grazing pressures.

Soil testing and management: Regularly test soil to manage nutrient levels, adding nitrogen or other amendments as needed to improve forage growth.

Advanced Metrics and Calculation Tools

When assessing the carrying capacity for cattle in Massachusetts, property owners can benefit from understanding advanced metrics such as utilization rate and forage demand. These tools are critical for estimating the appropriate stocking density and ensuring that the pasture can support the livestock without becoming overgrazed.

Utilization Rate and Forage Demand

Utilization Rate refers to the percentage of available forage that cattle will consume. It is a crucial element in calculating forage demand and, consequently, the stocking rate. To manage grazing sustainably, a common guideline is to allow livestock to consume up to 25-30% of the pasture's forage, leaving the rest to support plant health and ecosystem balance.

Forage Demand encompasses the total amount of forage necessary to meet the needs of the cattle over a specific period. This is often measured in Animal Unit Days (AUD), where one AUD equates to the amount of forage one 1,000-pound cow will consume in one day (usually estimated at about 26 pounds). For precise planning, property owners calculate the forage demand as follows:

[ \text{Forage Demand (lbs)} = \text{Number of Animals} \times \text{Average Weight per Animal (lbs)} \times \text{Daily Forage Consumption Rate (lbs)} \times \text{Grazing Days} ]

Pasture Inventory is an evaluation of the available forage within a pasture. This inventory includes not only the quantity but also the quality of the forage, as different types of grasses and plants will offer varying levels of nutrients.

In Massachusetts, where the climate and forage types can impact forage production, using these advanced metrics can help farmers tailor their stocking rates to local conditions. Taking into account factors like grazing days and forage consumption provides a more accurate calculation when determining stocking density, the number of cows a pasture can support per acre. By leveraging these advanced calculation tools, livestock producers can optimize their grazing strategies and maintain the long-term productivity of their pastures.

Economic and Environmental Considerations

Determining the appropriate number of cows per acre on a property in Massachusetts entails analyzing both economic viability and environmental impact. Livestock management hinges on balancing profitability with the stewardship of natural resources.

USDA Economic Research Service Data

The USDA Economic Research Service provides crucial data on livestock economics, including carrying capacity and forage utilization rates. In Massachusetts, these figures are essential for farmers to understand the financial implications of their stocking rate decisions. For instance, inappropriate stocking rates can lead to increased production costs due to overgrazing, supplemental feeding, and soil degradation.

Carrying Capacity: This refers to the maximum number of livestock that can be sustainably supported based on available resources.

Forage Utilization: Efficient use of available forage can reduce the need for costly feed supplements.

Balancing Production with Ecological Sustainability

To ensure that management practices are both economically sound and ecologically sustainable, farmers must carefully assess:

Soil Health: The vitality of soil influences forage production and, by extension, stocking rates. Overgrazing can lead to soil erosion, nutrient depletion, and decreased pasture productivity.

Stocking Rate: Setting a stocking rate within the carrying capacity of the property is critical. It ensures that the forage base is not overburdened, which could otherwise lead to reduced animal performance and soil degradation.

Management Practices:

Rotational grazing to improve forage recovery and maintain soil health.

Periodic assessment of pasture conditions to adjust stocking rates as needed.

In summary, economic and environmental considerations in stocking rate decisions are interconnected. Utilizing USDA Economic Research Service data enables Massachusetts farmers to align stocking rates with carrying capacity and forage utilization to optimize economic returns while maintaining the ecological integrity of their lands.

Conclusion

Determining the appropriate stocking rate for cattle in Massachusetts depends on various factors including forage availability, land size, and pasture management practices. Landowners must assess their property's carrying capacity to ensure a sustainable grazing system.

Forage Production: Adequate forage production is crucial. Property owners should evaluate soil health, plant species, and growth rates to estimate the forage yield of their land.

Stocking Density: Cattle needs and the recommended stocking density can vary. A general guideline for a starting point is the use of an Animal Unit (AU) concept, where one AU represents a 1,000-pound cow with a calf.

Land Size: The size of the property will directly influence how many cows it can support. It's important to calculate the acreage needed per AU based on forage production and desired stocking rates.

In Massachusetts, the specific environmental conditions, such as soil type and climate, play a pivotal role in determining the optimal number of cows per acre. For instance, a higher stocking rate may be possible on rich pastureland with a long growing season compared to sandy soils with limited forage growth.

Accuracy in these estimations cannot be overstated. A balance between livestock numbers and forage availability is essential to maintain pasture health and prevent overgrazing. Properly managed stocking rates will lead to healthier cattle, improved pasture longevity, and potentially greater profitability in the long term. Therefore, landowners must be diligent in their calculations and willing to adjust as necessary.