When Substitutions Fail: Understanding Texture and Chemistry in Culinary Techniques

When substitutions fail, texture often suffers because the chemical properties of ingredients aren’t interchangeable, even if they appear similar. Common kitchen swaps like using regular sugar in place of powdered sugar or switching out fats may save a trip to the store, but they can produce unexpected results—grainy cookies, tough cakes, or split sauces. The science behind these failures usually comes down to differences in how ingredients influence structure, moisture, and binding during mixing and baking.

The visible and tactile qualities of food are influenced by molecular interactions that are not always obvious at first glance. In both home baking and food manufacturing, getting the right texture means understanding the underlying chemistry, not just the surface similarities between ingredients.

Exploring why certain substitutions go wrong helps explain why some recipes turn out perfectly while others disappoint. Readers looking to improve their baking or avoid culinary mishaps can benefit from understanding the science behind ingredient behavior.

Foundations of Food Texture and Chemistry

Understanding how foods deliver their characteristic textures depends on knowing their structure at both the chemical and physical level. The arrangement and interaction of ingredients defines not only mouthfeel and appearance but also how foods react to substitutions.

Texture and Food Science

Food texture results from a combination of physical structure and chemical interactions within ingredients. Components like starches, proteins, and fats create textures ranging from creamy to crunchy. Processing techniques—mixing, baking, or freezing—alter these structural features.

Measurement of food texture involves rheology and sensory analysis. Objective tests include hardness, cohesiveness, and viscosity, while sensory panels describe properties like crispness or chewiness. Even small changes in formulation, such as swapping one fat for another, can lead to significant changes in perceived texture.

Common Texture Attributes:

Attribute Example Crunchy Crackers, chips Smooth Yogurt, custard Elastic Bread, mochi

Texture is fundamental in how foods are accepted or rejected by consumers.

Chemical Compounds in Food Ingredients

The molecular makeup of food ingredients significantly influences both flavor and texture. Common compounds include proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and water, each playing distinct roles.

Proteins help form gels and networks, as in cheese or tofu.

Carbohydrates such as starch and cellulose provide structure and impact viscosity.

Fats and oils contribute to mouthfeel and moisture retention.

Chemical reactions like gelatinization, emulsion, and enzymatic browning modify these compounds during cooking. For example, when starch gelatinizes in water, it transforms from a granular solid into a thickened paste, altering the final dish's texture.

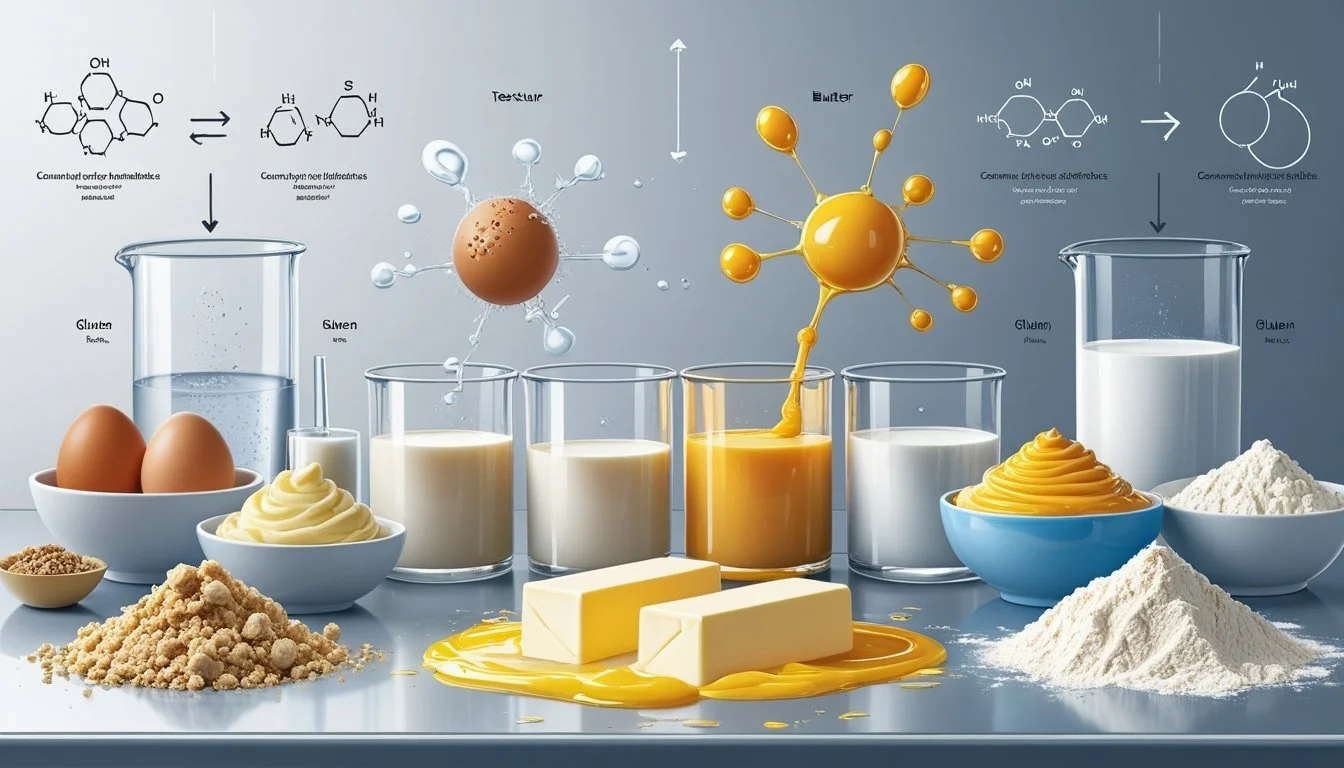

The Role of Phases and Colloids

Most foods are complex systems of multiple phases—solid, liquid, and sometimes gas. These phases may exist together as colloids, such as emulsions, foams, or gels.

Emulsions: Mayonnaise and salad dressings, where oil droplets are dispersed in water.

Foams: Whipped cream, featuring gas bubbles trapped in a liquid.

Gels: Jellies, where a network of polymers traps water.

The stability and formation of these colloidal systems are essential in determining food texture. Factors like temperature, pH, and mixing influence whether a food’s phases remain discrete or combine successfully, dictating both shelf life and consumer enjoyment.

How Substitutions Affect Texture

Altering ingredients changes more than flavor; it influences how components interact at a chemical level. These changes can impact how ingredients stick together or move within mixtures, leading to noticeable differences in finished products.

Adhesion and Binding Properties

When swapping binders like eggs, gluten, or butter, differences in adhesion become clear. Traditional binders hold dough and batter together by forming either protein nets (as with gluten) or emulsions (such as eggs and butter fat). Substitutes like flaxseed meal, non-dairy yogurt, or margarine often lack the same adhesive strength.

Reduced binding can make cookies or cakes crumble easily. Table: Common Binders and Substitutes

Original Binder Typical Substitute Texture Effect Egg Flax or chia "egg" More crumbly, less cohesive Butter Vegan butter/oil Slightly softer, sometimes greasy Wheat gluten Oat or almond flour Denser, may fall apart

Some ingredients, such as cream cheese, have lower fat content and do not bind as well, sometimes resulting in a hard or brittle product.

Impact on Viscosity and Suspension

Ingredient swaps can alter viscosity, or the thickness and flow of batters and doughs. For example, using oil instead of butter increases liquid content, making mixtures looser and less able to suspend solids like chocolate chips or nuts.

Higher viscosity keeps particles evenly distributed. If the binder doesn’t thicken enough, solids may sink or clump, leading to uneven texture.

Non-dairy milks or low-fat substitutes reduce overall viscosity, hindering the suspension of air bubbles or flour particles. This can yield baked goods that are dense, gummy, or unevenly textured.

Chemical interactions also matter: sugar substitutes dissolve and interact differently, affecting structure and suspension inside the dough.

Common Ingredient Substitutions and Their Outcomes

Not all substitutes behave the same as the ingredients they replace. Differences in structure and function can lead to changes in recipe texture, flavor, and stability.

Egg Substitutes: Challenges and Effects

Eggs offer structure, binding, moisture, and leavening to recipes. Popular substitutes include mashed banana, applesauce, silken tofu, chia seeds, and aquafaba (chickpea brine).

Each substitute interacts with the recipe’s texture differently. For example:

Mashed banana or applesauce: Adds moisture but can cause denser, sweeter baked goods.

Silken tofu: Binds well but makes a heavier crumb.

Chia seeds: Create a gelatinous texture, which can work for chewy baked products but adds a mild, earthy taste.

Aquafaba: Can whip like egg whites, suitable for meringues, but lacks the richness of yolk.

The most common problems are collapse, gumminess, or unbalanced flavor. Egg substitutes rarely provide the same lift, golden color, or crispness as real eggs.

Starches and Gums as Thickeners

Thickening agents such as cornstarch, arrowroot powder, and xanthan gum are used in place of traditional thickeners like flour or gelatin. Each option affects the final result in distinct ways.

Cornstarch: Produces a clear, glossy texture in sauces. It can break down if overcooked or exposed to acid.

Arrowroot powder: Tolerates acid and freezing well, but can yield a slippery mouthfeel.

Xanthan gum: Used in small quantities, stabilizes gluten-free batters but can create a slimy or gummy texture if overused.

Gelatin: Aids in setting desserts, but plant-based alternatives like agar or pectin can result in different firmness and clarity.

Combining gums or starches sometimes helps, but getting the right balance often takes trial and error. Measuring carefully and matching the thickener to the dish’s needs is critical for acceptable results.

When Substitutions Go Wrong: Case Studies

Substituting ingredients in baking and cooking can lead to unexpected changes in texture, flavor, and even food chemistry. Understanding real-world failures helps identify why certain swaps don't always produce the desired results.

Faulty Texture in Baked Goods

Swap baking soda for baking powder, or vice versa, and the outcome can shift dramatically. Baking soda is a base and needs an acid to activate, while baking powder includes its own acid. Using the wrong one can result in dense, flat, or oddly flavored brownies.

^

Baking Soda Baking Powder Needs acid (e.g., vinegar, buttermilk) Already contains acid Reacts quickly May have double-action Adds a distinct taste Neutral flavor

When butter is swapped with oil, cakes may become greasy rather than tender. Replacing eggs in brownies can cause them to lose their structure and become crumbly. The exact chemistry of each substitute often fails to mimic the original, impacting the final result.

Cheese and Dairy Alternatives

Switching classic cheeses for plant-based alternatives can compromise both melt and mouthfeel. Vegan cheeses made from starches or nuts may not stretch, brown, or blend like dairy versions. The result is often a rubbery texture and muted flavor.

When cream cheese is replaced with tofu blends in frostings, the mixture can become watery, missing the thick, creamy texture needed for piping. Pizza made with almond- or soy-based cheese alternatives often fails to brown, remaining pale and soft.

Texture, melting point, and water content are critical. Dairy products contribute to browning through the Maillard reaction—often absent in many non-dairy formulations.

Yogurt, Buttermilk, and Acidic Ingredient Replacements

Recipes calling for buttermilk or yogurt often rely on their acidity to activate leavening agents like baking soda. Swapping these with milk plus vinegar can work, but sometimes lacks the thick consistency or tangy taste.

If yogurt is replaced with non-dairy versions, water separation may occur, producing a thinner batter that struggles to bake up light and fluffy. In pancakes, using plain milk instead of buttermilk often leads to less rise and a dense texture.

Vinegar is sometimes added as a quick fix, but cannot replicate the mouthfeel and body provided by traditional cultured dairy. The balance of fats, proteins, and acids in real yogurt or buttermilk creates unique textures difficult to replicate precisely.

Understanding Flavor Profiles and Food Chemistry

Changes to ingredients can alter how flavors develop and interact, affecting the perception and stability of the finished dish. Chemistry plays a central role, particularly when substituting fats, thickeners, or solvents.

Flavor Development in Substituted Foods

Substituting ingredients often shifts the balance of volatile compounds that define flavor profiles. For example, replacing butter with oil modifies not only the lipid structure but also the aroma and mouthfeel, due to differences in the types of fats and their breakdown during cooking.

These changes can reduce or enhance specific notes, such as diminishing buttery or milky flavors. Substitutes might lack key precursors necessary for Maillard reactions, which are crucial for browning and the formation of complex aromas.

Texture also affects flavor delivery. If a substitute alters the matrix of a food—such as changing gluten in baked products—this can impact how volatile compounds are released, perceived, and enjoyed. Table 1 shows selected common substitutions and their impact on flavor:

Original Ingredient Common Substitute Flavor Change Butter Vegetable Oil Less richness, flatter Whole Milk Soy Milk Beany notes Sugar Stevia Bitter/metallic taste

Emulsions, Solvents, and Food Stability

Emulsions contribute to food stability and mouthfeel by blending immiscible liquids, like oil and water. The choice of emulsifier and fat source influences flavor release: some emulsions may mask or amplify certain aromas.

When solvents are swapped—such as replacing water with alcohol in extracts—the solubility of flavor compounds changes. Alcohol is a better solvent for many aromatics, so switching to water can reduce extraction of key flavor molecules, diminishing the intended profile.

Food stability is closely tied to chemical interactions. Substituting a stabilizer in a salad dressing emulsion may cause separation or rapid spoilage. These factors directly affect shelf life, texture, and how consistently flavors are experienced across each bite. Proper selection of emulsifiers and solvents is essential for maintaining intended flavor and texture.

Nutritional and Health Consequences

Substituting ingredients in food products can affect both their nutritional value and potential health impacts. The presence or absence of certain nutrients, as well as the physical form of a food, can change how the body responds during digestion and absorption.

Nutritional Aspects of Food Substitutes

Ingredient substitutions often aim to reduce calories, sugar, or fat. However, these swaps can lead to losses in essential vitamins, minerals, and fiber. For example, using refined flour instead of whole grain reduces B vitamins and dietary fiber.

The matrix of a food—the way nutrients are organized with carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—affects how nutrients are absorbed. Liquid and solid food forms can change satiety and glucose responses. Substituting whole foods with processed versions may lower nutritional density.

A simple table outlines common substitutes and typical nutritional differences:

Substitute Example Main Change Possible Nutritional Impact Margarine for butter Type of fat More trans fats, fewer vitamins Non-dairy for dairy Protein, calcium Lower in protein/calcium, may add sugar Artificial sweetener Sugar content Fewer calories, no fiber or minerals

Health Benefits and Limitations

Some substitutions offer health benefits, such as lowering saturated fat or decreasing added sugar. For people with allergies or intolerances, alternatives can reduce risk of reactions and improve dietary inclusion.

Despite these positives, substitutes often have drawbacks. Ultra-processed substitutes can contain additives and preservatives that affect gut health or metabolic function. Highly refined products may spike blood sugar or lack important phytonutrients.

Texture changes from substitutions may also alter eating habits or lead to reduced satiety. This can influence appetite control and may contribute to overeating if satisfying texture and bulk are missing.

Shelf Life and Environmental Impact

Changing an ingredient can significantly impact both the longevity and sustainability profile of a product. Understanding these factors helps producers and consumers recognize the trade-offs in shelf stability and ecological footprint.

Shelf Life of Substituted Products

Altering key ingredients—such as swapping eggs for flaxseed or wheat flour for almond flour—often changes how long a product remains safe and appealing. Many substituted products are more prone to spoilage, particularly when unfamiliar combinations alter moisture levels or pH balance.

Microbial growth can accelerate with some substitutions, reducing shelf life and increasing waste. For example, plant-based fats may oxidize faster than traditional animal fats, leading to off-flavors and textural decline.

Packaging and storage may also need adjustment. Products with alternative binders or reduced preservatives may require refrigeration to avoid premature spoilage. The loss of certain chemical barriers, such as salt or sugar, further increases the risk of microbial spoilage and physical changes—like staling or sogginess—according to current food science literature.

Environmental Considerations in Ingredient Choices

Substituting ingredients can decrease or increase a product’s environmental impact. Some alternatives, such as plant-based proteins or upcycled ingredients, can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and land use compared to animal-derived inputs.

However, not all substitutes are equal. For instance, almond flour production requires more water per kilogram than wheat flour, while coconut oil entails long-distance transport and deforestation concerns. The sourcing and processing of specialty ingredients may result in increased energy use, transport emissions, or habitat loss.

Manufacturers and consumers should weigh these effects using tools such as life cycle assessment. Sustainable substitutions often involve local ingredients with minimal processing, reducing both carbon footprint and ecological strain.

The Science Behind Successful and Failed Substitutions

Substituting ingredients in recipes can lead to unexpected changes in texture and chemistry. The process often depends on expertise, controlled testing, and a detailed understanding of how ingredient properties interact.

Role of Food Scientists and Research

Food scientists apply chemistry and biology to predict how ingredient swaps impact a product's structure, taste, and shelf life.

They examine physical and chemical similarities when evaluating substitutes. For instance, a fat replacement must not only mimic flavor but also provide moisture and aeration. If these roles are not chemically compatible, the result may be dense or crumbly.

Research in the food industry includes controlled experiments, where each variable is tested separately. Successful substitutions usually follow scientific criteria:

Criteria Example Similar protein Replacing eggs with aquafaba Fat content Swapping butter for oil Reaction to heat Substituting baking powder

Published case studies help validate effective ingredient replacements, creating best practices for both commercial and home kitchens. Failures are often traced to overlooked variables, such as moisture retention or gluten formation.

Trial and Error in Recipe Development

Trial and error is a key part of the substitution process, especially outside the lab.

Recipe developers and chefs commonly make incremental changes, noting the effects on texture, flavor, and appearance. A flour substitution, for example, may require several attempts to balance hydration and structure.

Failures highlight limitations in substitution. For example:

Using applesauce in place of fat may give a gummy texture.

Replacing all-purpose flour with non-wheat flours can disrupt gluten networks, leading to collapse or excessive crumbling.

Iterative testing is essential. Each test reveals more about which ingredient functions cannot be replicated, helping fine-tune substitutions for better texture and reliability.