A Simple Guide to Umami

Discover > Texas Home Cooking > A Simple Guide to Umami

Do you know the taste of umami? Let’s explore here the “essence of deliciousness.”

It wasn’t long ago that I was in school still being fed the same inaccurate information about taste buds and flavors that I still see a lot of today, particularly the one that says certain taste buds reside on certain areas of the tongue. While sweet, salty, bitter, and sour have been intricate parts of every cuisine across the world since man first made a fire, it wasn’t really until around 100 years ago that we really began to understand.

The Taste of Umami and the 5 Basic Flavor Profiles?

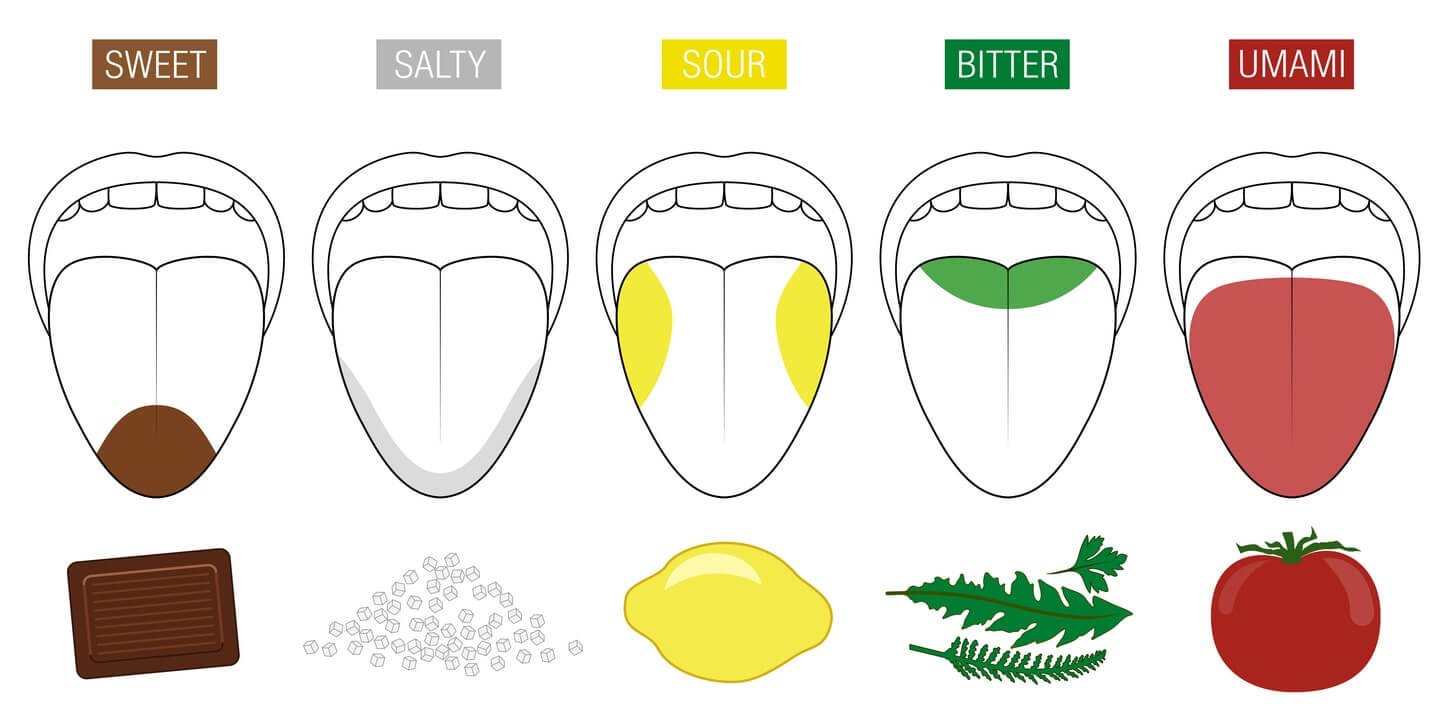

Sweet, salty, bitter, sour, or umami (savory) is how we describe pretty much any food or drink you can imagine. They are determined by the different taste receptors we have on our tongues (there are 5 different types). Alongside those are piquant (a fancy word for spicy) and fatty. In order for a food to taste good all of these things have to be in balance, because like when something is too sour, a super intense umami flavor is also off-putting (that’s the key to being an amazing chef, by the way. Balance).

Out of all of those umami is most likely the first one you ever come into contact with after you were born. Studies have shown that over half the free amino acids in breast milk are the ones that stimulate the umami sensation on our tongue (more about that later).

What are Umami Taste Buds?

Umami is more a word to describe the sensation of when certain taste receptors (mGluR4 and mGluR1 receptors) respond to particular glutamates and nucleotides naturally (and in more recent years synthetically) occurring in food like meat, broth, seaweed, mushrooms, truffles (What wine goes well with truffles?), and certain vegetables. Stimulating these receptors is what causes our mouths to water when we’re walking down a market smelling the street vendors' freshly wrapped burritos.

Who Discovered the Taste of Umami?

Glutamates have been used in cooking since the first colonies started to pop up in china millennia ago. Fermented meats & vegetables and sauces (like fish or soy sauce (how long does soy sauce last?)) were used by practically every culture from the Mongolians to the Byzantines and Arabs, all the way through to the Roman empire.

It wasn’t until 1908 when Kikunae Ikeda, a professor at Tokyo Imperial, found abundant glutamates in kombu (how long does kombu last?) seaweed broth after observing that the broth was neither sweet, salty, bitter, or sour.

In 1913 Ikeda’s predecessor, Professor Shintaro Kodama found another substance that stimulates the umami receptors. He found that the ribonucleotide, IMP, was also abundant in dried bonito flakes (a Japanese fermented tuna dish).

In 1957, Akira Kuninaka, a Japanese Agricultural chemistry researcher, realized that the ribonucleotide GMP present in shiitake mushrooms also conferred the umami taste. He also discovered the synergistic effect between ribonucleotides and glutamate and that when combined, makes the umami sensation much more intense.

Today food manufacturers are constantly synthetically enhancing the flavor of food using these glutamates and nucleotides, most notably the ‘big bad’ MSG or monosodium glutamate (psst, if it was that bad for you half of China would be sick and dying).

Food Rich in Umami Compounds

Different foods create a taste of umami through many different combinations of glutamates and nucleotides. While the amino acid normally responsible for it is L-glutamine (an a-amino acid used by all living things responsible for synthesizing protein in the body) the nucleotides can vary quite a bit. A few very common ones are IMP (inosine monophosphate primarily present in meat and meat extracts), GMP (Guanosine monophosphate most present in umami vegetables), and AMP (Adenosine monophosphate most abundant in fish and other seafood).

These umami combinations are most notable (particularly L-glutamate, IMP, and GMP) in fish, shellfish, cured meats (What wine goes well with cured meats?), meat extracts, mushrooms, vegetables (e.g., ripe tomatoes, Chinese cabbage, spinach, celery, etc.), green tea, hydrolyzed vegetable protein, and fermented and aged products involving bacterial or yeast cultures, such as cheeses, shrimp pastes, fish sauce, (how long does fish sauce last?) soy sauce, nutritional yeast (how long does nutritional yeast last?), and yeast extracts such as Vegemite and Marmite.

Synthetic Umami

What umami tastes like? Using the compounds that create umami to improve the flavor of low-sodium foods, in particular, has become incredibly popular. While The FDA has designated the umami enhancer monosodium glutamate (MSG) as a safe ingredient, people still seem to go nuts (how long do nuts last?) over it going as far as to claim they are sensitive to it. You would have to eat an insane amount of MSG (pounds and pounds in one sitting) for it to be anywhere near fatal, which can be said for pretty much anything.

The number of taste categories there are is very widely debated. After all, umami taste buds weren’t properly discovered, studied, and applied until just a few decades ago and there’s still a lot we don’t know and a lot to explore about the taste of umami. Many people already consider piquant to be one of these taste categories. Some people believe there are upwards of 14 categories and some people even claim there are even infinite amounts.