Ancient Rome’s Relationship with Meat

Dietary Habits and Cultural Significance

Meat played a distinct but limited role in the diet of ancient Rome, reflecting both social class and cultural values. While wealthy Romans could indulge in a wide range of meats such as chicken, game birds, wild boar, and even exotic animals, most citizens—especially the plebs—primarily relied on bread, vegetables, cheese, and modest portions of meat when available. Soldiers’ rations included some meat, usually salt pork or bacon, but their main sustenance came from grains and legumes.

Roman attitudes toward meat were influenced by accessibility, expense, and sometimes even moral or philosophical beliefs favoring restraint. Some prominent figures discouraged frequent meat consumption, viewing it as a luxury or unnecessary indulgence. This layered relationship with meat helps reveal much about Roman society, daily life, and the evolving food culture across the Roman Empire.

Importance of Meat in the Roman Diet

Meat was present in the Roman diet, but its availability, cultural meaning, and daily significance differed by social class. While pork, birds, and fish were part of their food habits, cereals, vegetables, and legumes remained the foundation of most meals.

Role of Meat as a Status Symbol

In ancient Rome, meat consumption was closely linked to wealth and social rank. The upper classes frequently enjoyed pork, especially sausages, alongside game such as hare or boar, and various kinds of poultry. This access allowed them to host banquets that showcased rare meats, a clear display of status.

Most common citizens, especially the poor, had limited access to fresh meat. Their consumption was often restricted to festival days or special occasions, when meat might be distributed at public events. For them, regular intake of meat was rare.

Table: Access to Meat in Ancient Rome

Social Class Meat Access Common Types Elite/Wealthy Frequent Pork, game, poultry Poor/Commoners Occasional Pork (rare), offal

Comparison with Other Staples

Cereals, mainly wheat and barley, formed the backbone of the Roman diet for nearly all social classes. Foods like bread, porridge (puls), and sometimes pasta-like noodles were consumed daily. Vegetables, olive oil, and wine completed their staple intake, all widely available and affordable.

In contrast, beef was not widely eaten, as cattle were primarily used as draft animals rather than food. Meat was never as central as grain, but when available, it complemented grain-based dishes by adding extra flavor and nutrition. Despite the attention given to feasts, the average Roman relied daily on plant-based staples.

List: Key Staples in the Roman Diet

Cereals (wheat, barley, spelt)

Legumes (lentils, beans)

Vegetables (cabbage, onions, turnips)

Olive oil and wine

Protein Sources Beyond Meat

Romans obtained protein from a range of sources apart from meat. Legumes, especially lentils and chickpeas, were an important and regular part of the diet for all classes. Eggs and cheese also contributed significantly, providing reliable protein and fat.

Fish and other seafood were common, especially near rivers or the Mediterranean coast. Salted, dried, or pickled fish helped preserve protein and were more accessible than fresh meat for many people. Even for those who rarely ate pork or poultry, these alternatives ensured protein was a consistent dietary component.

Types of Meat Consumed in Ancient Rome

Ancient Romans had access to a variety of meats, with preferences and availability depending on social status, wealth, and regional customs. The selection ranged from common livestock to exotic and wild species, reflecting cultural attitudes and culinary innovation.

Pork and Its Popularity

Pork was the most widely consumed meat in ancient Rome, valued for its versatility and the large size of pigs. Roman farmers bred several types of pigs, producing different cuts and sausages to meet diverse culinary needs.

Dishes such as porcellum hortolanum (garden-raised piglet) and blood sausages were regular features at banquets. Salt-cured hams and various forms of bacon were also part of daily life. Wealthier Romans enjoyed roasted suckling pig as a delicacy.

Pigs were efficient to raise, offering a high yield of meat for urban and rural dwellers alike. The entire animal, from snout to tail, was often used, reflecting Roman thrift and ingenuity. Pork fat, especially lard, played a vital role in cooking.

Poultry and Game Birds

Poultry included chicken, duck, goose, and capon, each occupying a place at Roman tables depending on the occasion and budget. Chicken was common and could be found in both elite and modest households, while ducks and geese were reserved for more affluent families.

Game birds such as pheasant, thrush, woodcock, and starling were considered delicacies, often served at feasts and special events. These were hunted or farmed in rural estates for wealthy citizens.

The consumption of game birds often served as a display of status due to their cost and rarity. Romans also practiced breeding of birds, such as pigeons and doves, to ensure a steady supply. Each variety was often prepared with unique sauces or seasoning blends.

Beef, Veal, and Mutton

Cattle were primarily raised as draft animals, so beef was not as prominent as pork or poultry in the Roman diet. When consumed, it was usually from older animals that had finished their working lives, making the meat tougher and less desirable for fine dining.

Veal, on the other hand, was prized among the wealthy. Tender and pale, veal dishes appeared frequently at banquets.

Lamb and mutton were more associated with rural populations and certain regions, but they were nonetheless a key part of Roman cuisine. Goats also provided meat and were common in areas where sheep farming was less viable. Both mutton and goat were often roasted or stewed.

Exotic Meats and Wild Game

The Roman elite sought out exotic meats to showcase their wealth and adventurous palate. Dormice were a luxury snack, fattened in special jars and served stuffed with herbs or nuts. Ostrich, though rare, was imported and sometimes featured at imperial banquets.

Hare, wild boar, and deer were among the most popular forms of wild game. These animals were prized for their flavor and often hunted on aristocratic estates.

Serving wild game was a symbol of refinement and affluence. Preparations often involved elaborate presentations and rich sauces, highlighting both the skill of the cook and the status of the host.

Sources and Supply of Meat

Meat reached Roman tables through a mix of direct production, organized hunting, and commercial trade. Its availability was shaped by social status, geography, and the systems that connected producers to consumers.

Farming and Animal Husbandry

Farming formed the backbone of Rome's domestic meat supply. Livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs were raised on both small farms and large estates. Wealthy landowners with extensive properties could afford animals primarily for slaughter, while smaller farms prioritized secondary resources like milk and wool.

Slaves provided much of the labor required for animal care and daily farm tasks. Animals were raised for both local use and for city markets, with pigs often favored due to their quick growth and ability to thrive on food scraps. The use of dovecotes for birds and specialized towers for dormice added variety to Roman diets.

Key points:

Livestock raised: cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, poultry, dormice

Labor: largely dependent on slave workforce

Focus varied by estate size (meat production vs. by-products)

Hunting and Wild Game Acquisition

Wild game represented an important but less regular source of meat. The forests and countryside around Roman settlements contained deer, boar, hares, and numerous birds. Hunting was a privilege for the elite, who enjoyed it both as a sport and a source of fresh meat for their households.

Roman hunters used nets, traps, and trained dogs to capture both small and large animals. Game was sometimes supplied to city markets during seasonal surpluses, though it remained less accessible to ordinary citizens. The capture and raising of birds, as well as dormice, often connected the wild and domestic supply chains.

Small mammals and birds were sometimes kept in specially designed enclosures, bridging the gap between hunting and farming practices.

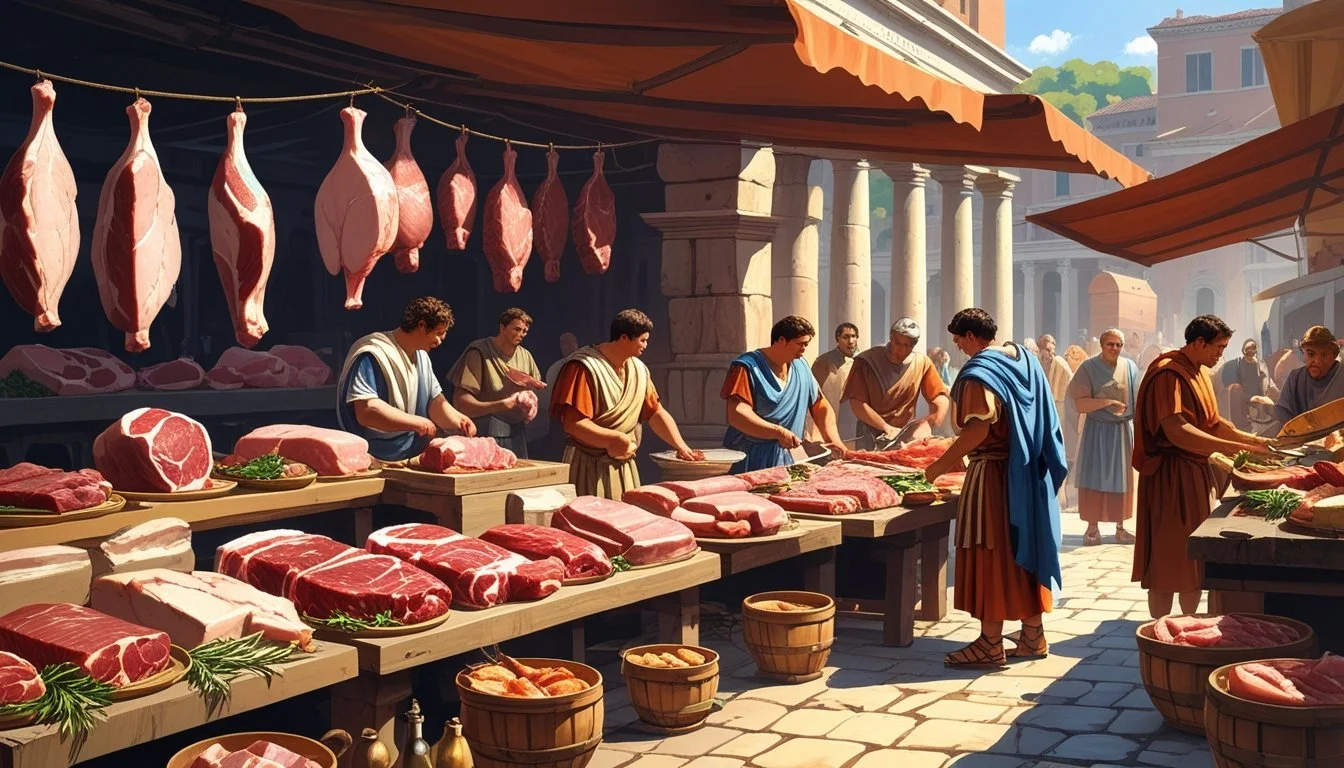

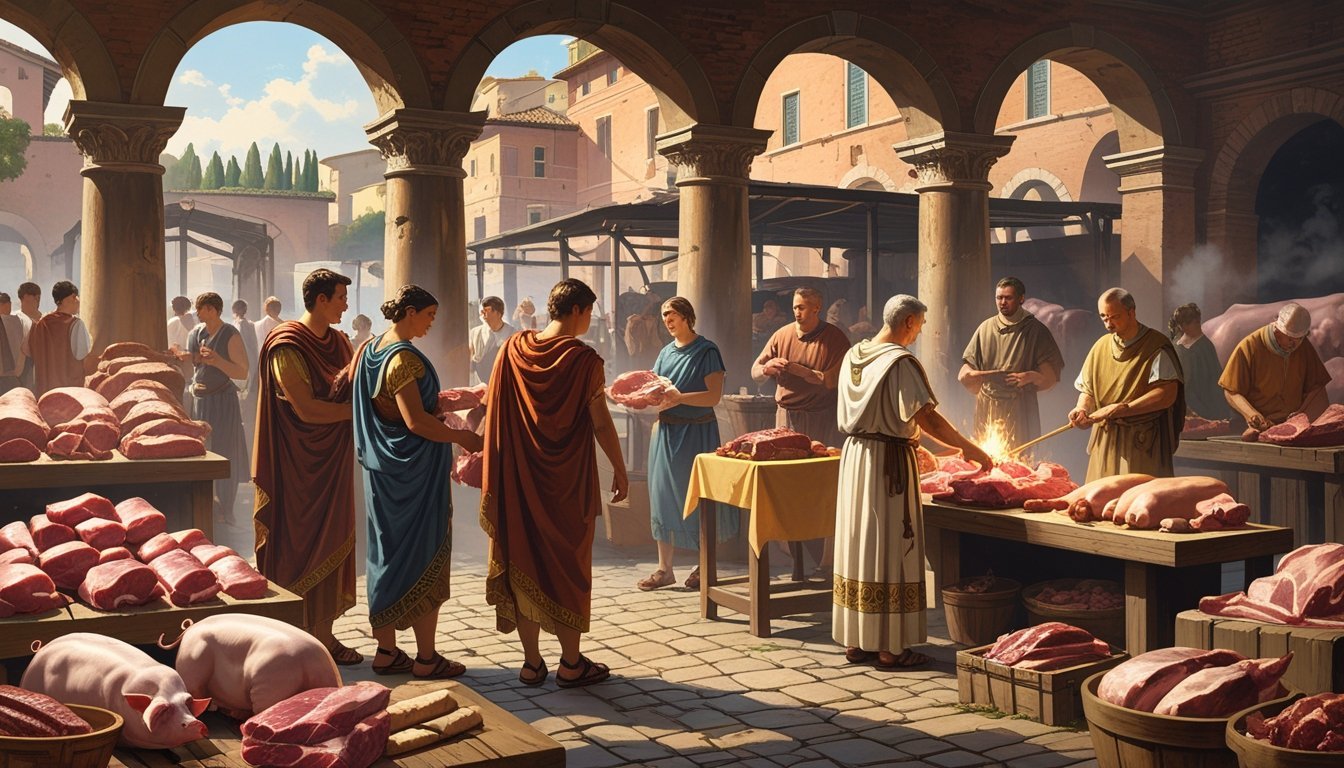

Trade, Markets, and Food Supply

Urban demand for meat required a robust trade and market system. Farmers and rural producers brought livestock to city gates, where animals were slaughtered and their meat sold at city markets and stalls. Regular markets offered cuts of beef, pork, goat, mutton, and poultry.

Vendors, butchers, and taverns sold both raw and prepared meats, meeting different consumer needs. Imported meats were uncommon but did occur, especially for luxury banquets and the elite. Religious festivals and state distributions sometimes provided meat to lower classes, especially in Rome itself.

A summary table of primary sources:

Source Example Meats Consumer Access Local farms/estates Pork, mutton, beef Common, elite Wild game Deer, hare, birds Mostly elite Market trade Mixed meats Broad urban populace

Methods of Meat Preparation and Cooking

Ancient Romans approached meat preparation with a combination of practicality and culinary sophistication. They used varied cooking methods, distinctive seasonings, and inventive recipes that shaped Roman cuisine for generations.

Popular Cooking Techniques

Roasting was a common practice, especially for larger cuts of meat such as pork, lamb, and game. Meats would be skewered on spits and cooked over open flames or in hearths.

Boiling and stewing were frequent choices for tougher cuts. Using large bronze or clay pots, Romans simmered meats with water, wine, or stock for several hours. Grilling and baking were also valued, especially in wealthier households equipped with dedicated ovens. For common people, street vendors and communal kitchens often prepared simple grilled meats.

Table: Common Cooking Methods

Method Typical Meat Used Equipment Roasting Pork, game Spits, open hearth Boiling Beef, mutton Cauldrons, kettles Grilling Fowl, sausages Grills, open fires Baking Fish, small cuts Ovens

Seasonings and Sauces

Romans relied on a wide assortment of seasonings to enhance their meat dishes. Salt and olive oil formed the base of most preparations, ensuring both flavor and preservation.

Herbs such as dill, coriander, and savory were used fresh or dried. Spices like pepper and cumin added depth, especially in dishes for the affluent. Perhaps the most distinctive Roman ingredient was garum, a pungent fermented fish sauce poured over meats or mixed into stews.

Vinegar was used to add acidity, while honey balanced savory flavors with sweetness. A typical Roman sauce might blend garum, olive oil, vinegar, herbs, and ground pepper, then be drizzled over roasted or stewed meats.

Recipes and Culinary Innovation

Roman cooks documented and tested a variety of complex meat recipes, reflecting both local traditions and influence from conquered lands. Apicius, a Roman cookbook author, described preparations such as isicia omentata (meat patties flavoured with pepper and garum) and boar roasted with figs.

Innovations included marinating meats in vinegar and honey or stuffing animals with herbs and spices before roasting. Chefs also developed sauces—mixtures of garum, wine, reduced must, and aromatic herbs—to accompany different meats.

Roman banquets often featured dishes prepared in layers or with decorative presentation, showcasing not only the cook’s skill but the influence of trade and empire on Roman culinary practices.

Preservation and Storage of Meat

In ancient Rome, storing meat was a necessity due to limited supplies and the risk of spoilage. Methods such as salting, smoking, and sealing preserved meat for transport and future use, especially in urban centers and the military.

Salting and Smoking

Salting was one of the most widespread preservation methods in Roman times. Meat was covered in salt to draw out moisture, which helped prevent bacterial growth and spoilage. The process required careful timing; over-salting could ruin flavor, while under-salting left the meat vulnerable to rot.

Smoking provided an additional layer of protection, especially for meats intended to last through warmer months. Meat was hung in smoky chambers, where the smoke inhibited bacteria and molded a hard, preserved exterior. This technique not only extended shelf life but also gave the meat a distinctive flavor.

Both salting and smoking enabled Romans to store meat for long periods, making it possible to feed soldiers and large urban populations. Salting was more common for pork and fish, while smoking was often reserved for sausages and certain cuts of beef.

Other Preservation Techniques

Romans also used other means to keep meat from spoiling. One practice was storing cooked meat in containers sealed with fat or oil; the fat formed a barrier blocking air and bacteria.

Pickling was another reliable method, where meats were submerged in brine, vinegar, or wine. This acidic environment slowed down spoilage and added flavor. Some cured meats were stored in honey, which acts as a natural preservative by inhibiting microbial activity.

Meat was sometimes dried in the sun or wind, particularly in rural areas with access to naturally arid conditions. Large estates and cities kept surplus supplies in cool cellars or specially designed granaries, though these were more effective for grains than for fresh or preserved meats.

Meat in Roman Meals and Social Life

Meat held a varied position in Roman diets, reflecting class, wealth, and social context. The ways Romans consumed meat shifted between formal banquets, everyday meals, and the bustling environment of taverns and street vendors.

Meat at Banquets and Lavish Feasts

Lavish banquets, or convivia, were common among the Roman elite and often served as stage for social and political display. Meat played a central role, showcasing both abundance and access to exotic goods.

Pork was the most favored meat, often prepared as roasts or in elaborate sausages. Dishes included wild game, venison, boar, and fowl like peacock or goose. The inclusion of seafood and rare meats, such as dormice or imported delicacies, was a sign of a host’s wealth.

At these feasts, guests reclined on couches and ate in multiple courses. Dishes were often enhanced with spices and imported ingredients. Presentation mattered; hosts strived to impress, making meat a symbol of their status more than everyday sustenance.

Everyday Consumption and Meals

For most Romans, especially the lower classes, meat was eaten infrequently and usually in small amounts. The typical daily meals—ientaculum (breakfast), prandium (lunch), and cena (dinner)—relied primarily on grains, legumes, and vegetables, with meat reserved for special occasions or festival days.

Pork, especially as sausage, was the most common type of meat available to modest households. Wealthier citizens might have more regular access to poultry, fish, and occasionally mutton or goat. Beef was rare and not favored.

Meat often appeared in stews or mixed with beans to stretch its use. On festival days, larger amounts of pork or other meats could be distributed as religious offerings or public rations. In daily life, animal protein often came from eggs, cheese, and fish rather than butchered meats.

Role of Taverns and Street Food

Taverns (popinae) and street food stalls were essential for the urban working classes who lacked private kitchens. These establishments offered accessible prepared foods, many of which included meat in some form.

Common offerings were sausages, offal, and stews made from cheaper cuts of pork or poultry. The quality and quantity of meat were modest but provided needed variety for those with limited means. Food was served hot, catering to laborers and travelers needing quick sustenance.

Taverns saw a mix of customers, from slaves to freedmen. They played a key role in spreading certain eating habits, popularizing affordable meat dishes. Meals were informal, eaten on the go, and typically included bread, wine, and whatever meat the day allowed.

Cultural, Religious, and Economic Influences on Meat Consumption

Ancient Rome’s approach to meat was shaped by distinct regional customs, trade connections, and religious beliefs. Economic disparities and social class also played major roles in dictating who could access which types of meat.

Regional Variations Across the Roman Empire

Diversity in meat consumption emerged as the Roman Empire expanded. In Egypt, fish and poultry were common, while beef was rare due to religious traditions. In Gaul (modern-day France), pork and game were favored, reflecting both local agriculture and cultural preferences.

Elite Roman households in Italy had access to a wider variety of meats, including imported delicacies from Spain. The climate, geography, and agricultural practices of each region determined what meats were available, leading to distinctive culinary habits across the empire.

Even within urban centers, social class influenced consumption. Wealthier Romans enjoyed a greater assortment of meats, while lower classes often relied more on legumes, grains, and occasional pork or mutton.

Influence of Trade and Conquests

Rome’s extensive trade routes and military campaigns introduced new animals and products into daily life. Trade with Egypt brought preserved fish and exotic spices, while conquests in Spain led to the import of particular breeds of cattle and sausages.

A simplified table summarizing key imported goods:

Region Major Meat-Related Imports Egypt Salted fish, waterfowl Gaul Pork, wild game Spain Beef, sausages, ham

Markets in Rome thrived on these imports, making once-rare meats accessible in urban centers. The flow of goods and animals influenced local tastes and transformed the Roman diet far beyond the Italian peninsula.

Religious Practices and Taboo Foods

Religious rituals in Rome often centered on animal sacrifice, especially cattle, sheep, and pigs. Meat from these sacrifices was shared in communal feasts, reinforcing social bonds and religious hierarchy.

Certain meats were restricted by custom or taboo. For instance, horse meat was generally avoided, except in specific provincial contexts. Abstention from some terrestrial meats during religious festivals or mourning periods was observed among certain groups, influenced in part by Mediterranean religious traditions.

Local beliefs in places like Egypt also shaped consumption. Sacred animals, such as the ibis or some cattle breeds, were protected, meaning their meat was seldom, if ever, eaten. These layered customs ensured that meat consumption remained closely connected to both Roman religious identity and regional diversity.

Comparison with Other Foods in Ancient Rome

Meat was just one component of the diverse Roman diet, and for most people, plant-based foods, grains, and products from the sea or dairy sources were far more common. Social status and wealth shaped food choices significantly, with daily meals for many centered around simple, accessible ingredients.

Grains and Bread as Staple Foods

Grains formed the core of the Roman diet, particularly for the lower and middle classes. Wheat and barley were the most widely cultivated grains, often ground into flour for bread or cooked as porridge (puls). Bread was so fundamental that it became almost synonymous with food itself in daily language.

Barley was considered less desirable than wheat but was a staple for the poor and soldiers. Puls, a thick porridge made from grains and legumes, appeared on many tables. Wealthier citizens might enjoy bread made from white, finely milled wheat flour, while commoners ate coarse, dark loaves.

Cereals provided the bulk of calories for most people. The importance of grains even extended to religious rituals and offerings, highlighting their central place in daily life.

Fruits, Vegetables, and Legumes

Fruits, vegetables, and legumes rounded out many meals, especially when meat was scarce or unaffordable. Fruits such as apples, pears, figs, cherries, and grapes featured widely and were eaten fresh, dried, or preserved in honey. Figs and grapes held special value, with grapes also used for making wine.

Vegetables like onions, garlic, cabbage, and leeks were common, and Roman gardens included a range of produce such as lettuce, celery, and turnips. Legumes—peas, chickpeas, broad beans, lentils, and beans—were highly valued for their nutrition and versatility.

These foods could be consumed alone, added to stews, or made into dips and spreads. For many Romans, dishes based on legumes spread on bread or combined with vegetables formed the backbone of the daily diet.

Fish, Seafood, and Dairy

Fish and seafood played a vital role, particularly in coastal regions and among the affluent. Romans enjoyed fish both fresh and salted, and delicacies like oysters, mussels, clams, and scallops were prized at elite banquets. Salted fish sauce (garum) became a signature Roman condiment and appeared at all levels of society.

Dairy products, especially cheese, were important protein sources. Milk was more commonly used for making cheese rather than for drinking directly. Cow, sheep, and goat cheeses varied in richness and flavor, and cheese was often eaten with bread or fruits.

Seafood and dairy provided essential nutrients otherwise lacking in a primarily grain-based diet. Their presence on the table signaled variety and, sometimes, higher social status.

Legacy of Meat Consumption in Roman Cuisine

Ancient Roman cuisine left a lasting mark on food culture in Europe. Diverse preparations and the social value of meat influenced both ingredients and traditions in later centuries.

Influence on Later European Diets

Roman meat-eating customs shaped medieval and Renaissance cuisine across Europe. Romans introduced new livestock breeds and butchery methods, and their use of pork, especially, remained central in many regions.

The Romans made widespread use of sausages, cured meats, and meat sauces. Dishes like lucanica (a type of sausage) and roast pork inspired many later recipes. Aristocratic banquets featuring roasted or stewed meats set expectations for elite dining throughout Western history.

Bread and meat combinations, such as small meat pies or filled breads, can be traced back to Roman origins. Their practices also promoted the use of offal and the whole animal, which persisted into early European cookery.

Surviving Recipes and Cooking Traditions

Many Roman recipes have survived through sources like Apicius’s De Re Coquinaria, the oldest known Roman cookbook. These texts document techniques such as roasting, stewing, and grilling, often paired with strong sauces and spices.

Common seasonings included garum (a fermented fish sauce), pepper, cumin, and lovage. Meat dishes often featured combinations of sweet and savory elements, such as honey or dried fruits with pork or lamb, which later appeared in medieval cooking.

Some Roman traditions, like stuffing meats or using wine reductions, still feature in Italian and Mediterranean recipes. Today, modern renditions of ancient Roman food are found in both historical reenactments and specialty restaurants.