Exploring the Ancient Origins of Human Carnivory

Evidence from Early Archaeological Discoveries

The shift towards meat-eating stands as a turning point in human evolution, shaping not only diet but also technology, behavior, and even brain development. Archaeological evidence shows that early humans began incorporating meat and marrow from large animals at least 2.6 million years ago, with the use of stone tools allowing them to access new food sources and nutrients. Some of the earliest signs of this dietary change are found alongside the first discoveries of lithic (stone) technology, directly linking the origins of tool use with the pursuit of animal remains.

Stable isotope analysis and faunal remains from ancient sites indicate a gradual but significant move from plant-based diets toward persistent carnivory. These findings highlight the adaptability and resourcefulness of early hominins as they began to rely more heavily on animal foods. This transition helped lay the foundation for the development of modern human societies and the expansion of our ancestors into diverse environments.

The Evolutionary Context of Human Carnivory

Human dietary evolution includes a shift to regular meat consumption, which influenced the physical and behavioral traits of early hominins. The adoption of carnivory set humans apart from other primates and drove key adaptations in brain size, social behavior, and foraging strategies.

The Emergence of Meat-Eating in Early Humans

The earliest archaeological evidence shows that early members of the genus Homo began incorporating significant amounts of meat and marrow into their diets about 2.6 million years ago. This change coincided with the development of stone tools, which allowed more efficient access to animal flesh and bones.

Scavenging and later active hunting provided a higher-calorie food source compared to a strictly plant-based diet. This dietary shift likely fueled increases in brain size and supported energy-intensive activities.

Researchers estimate that a shift to as little as 10–20% of dietary intake from animal sources marked a significant change in hominin foraging. This trend toward carnivory distinguished early humans from other apes and altered their evolutionary path.

Primate Evolution and Dietary Shifts

Most primates are primarily herbivorous, relying on fruits, leaves, and insects for nutrition. Rarely, some species like chimpanzees demonstrate opportunistic meat-eating by hunting small animals or scavenging, but these behaviors are infrequent.

Humans are unique among primates for their regular, substantial meat consumption. Unlike their closest relatives, human ancestors adapted technology, such as stone tools, to make animal tissues a routine dietary component. This allowed them to exploit new environments and food sources unavailable to other primates.

The divergence in dietary habits between humans and other primates is a key factor in the evolutionary distinction of the human lineage. Carnivory became a hallmark of human dietary adaptation.

Significance of Carnivory in Hominin Evolution

The incorporation of meat into the diet had profound evolutionary effects. Regular access to nutrient-dense animal foods supported the development of a larger brain, which requires more energy compared to the brains of other primates.

Social dynamics also changed as meat became a central resource. Sharing meat likely encouraged cooperation, communication, and the emergence of early social structures in hominin groups.

Key impacts of carnivory in human evolution:

Increased caloric and nutritional intake

Expansion into new habitats

Evolution of complex social behaviors

These changes set the foundation for many distinct aspects of hominin evolution and human adaptation.

Key Archaeological Sites and Discoveries

Research into human carnivory relies on archaeological sites where evidence of early hominin meat consumption has been preserved. Through analysis of stone tools, faunal remains, and sediment layers, scientists are able to trace changing behaviors and ecological adaptations across Africa.

Olduvai Gorge and Oldowan Hominins

Olduvai Gorge, located in northern Tanzania, is a foundational site for understanding early hominin carnivory. Excavations here have revealed numerous stone tools classified as Oldowan, dating to about 2.6 to 1.7 million years ago.

These tools are simple flakes and cores, but cut marks on animal bones associated with them indicate that Oldowan hominins engaged in systematic butchery. The presence of percussion marks and evidence of marrow extraction demonstrate active processing rather than mere scavenging.

Zooarchaeological assemblages at Olduvai, such as those from the FLK-Zinj layer, show clear patterns of defleshing and disarticulation. This suggests hominins were accessing meat and marrow, likely competing with other carnivores.

Kanjera South and Early Meat Consumption

Kanjera South, located near Lake Victoria in Kenya, offers some of the earliest evidence for sustained meat eating by Oldowan hominins. Dated to about 2 million years ago, this site provides well-preserved faunal remains with cut marks and percussion damage.

Archaeologists have identified bones from small to medium-sized ungulates, showing both butchery and marrow extraction. The distribution of modifications indicates hominins acquired and processed these carcasses on-site rather than obtaining only scraps left by predators.

The findings from Kanjera South support the argument that regular meat consumption was a dietary adaptation in early Pleistocene hominins. The evidence points to a behavioral shift from opportunistic scavenging to more active and systematic meat acquisition.

Findings from Turkana

The Turkana Basin in northern Kenya has yielded a wealth of archaeological evidence concerning early hominin dietary practices. At sites such as Koobi Fora and FxJj50, Oldowan tools and faunal remains have been unearthed in contexts dating back nearly 2 million years.

Bones with clear cut marks, impact fractures, and signs of marrow extraction have been discovered, indicating deliberate processing of meat-bearing carcasses. The stratigraphic context links these remains to hominin activities rather than to non-hominin carnivores.

Research at Turkana sites benefits from excellent geological preservation, allowing detailed reconstructions of past environments and hominin behaviors. The consistency of archaeological findings across the basin highlights the widespread nature of meat eating among early human relatives.

Other Significant African Sites

Beyond the major localities, several other African sites contribute important data to the archaeology of early carnivory. Sites such as Gona in Ethiopia and Sterkfontein in South Africa have provided Oldowan tools associated with butchered animal bones.

At Gona, stone tools and cut-marked bones date to about 2.6 million years ago, making it one of the oldest sites of its kind. Sterkfontein, famous for its hominin fossils, also preserves evidence that early members of the genus Homo processed animal remains.

Together, these sites expand the geographic and chronological range of documented meat consumption. Through multiple lines of evidence, including zooarchaeological assemblages and stone tool analyses, researchers continue to chart the evolution of carnivory in Africa’s early Pleistocene hominins.

Methods of Meat Acquisition and Processing

Early humans obtained meat through a combination of hunting, scavenging, and processing animal carcasses using evolving stone tool technology. These practices are documented by zooarchaeological evidence, including butchery marks and excavated animal bones, which provide insight into ancient methods.

Hunting Strategies of Early Humans

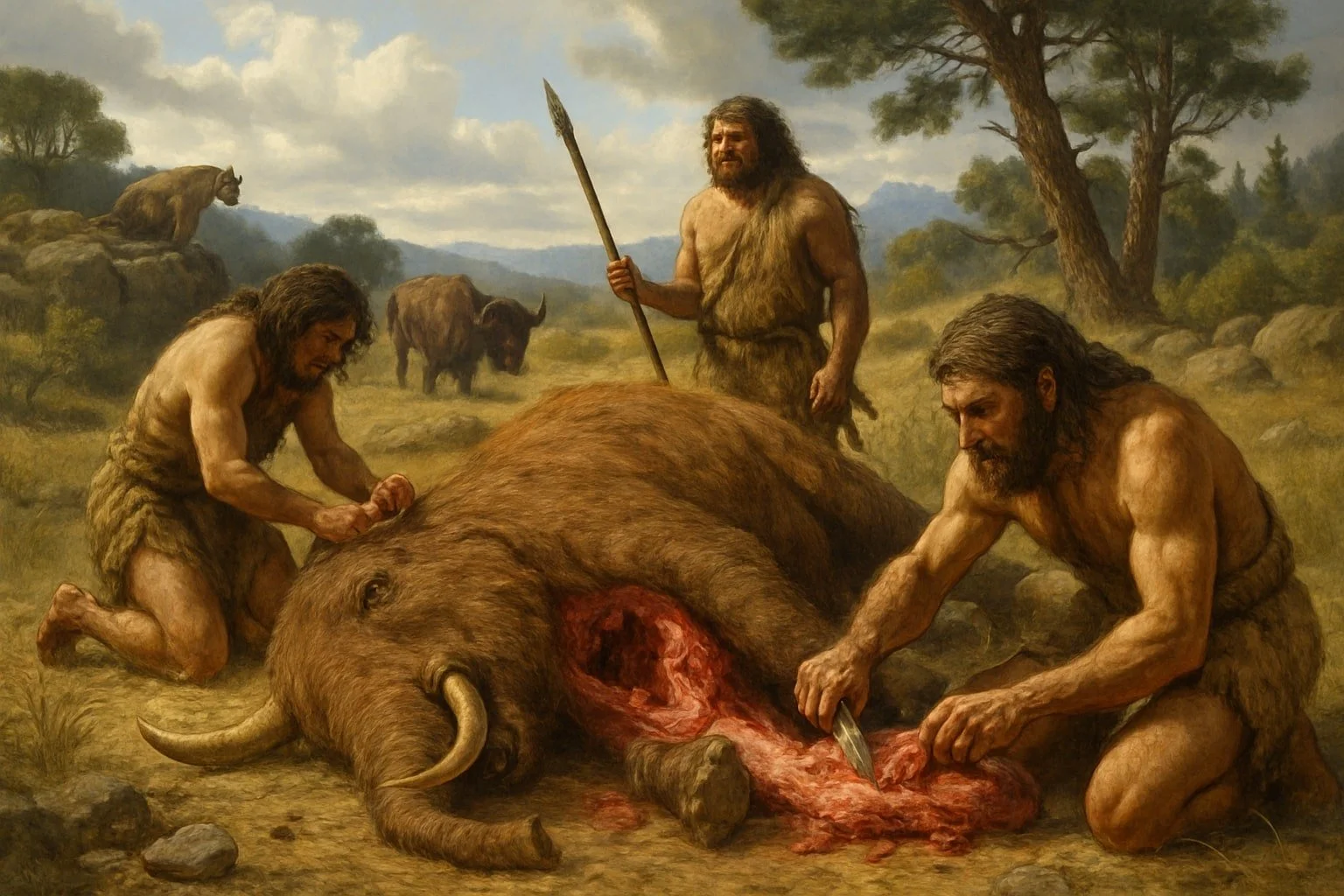

Hunting required planning, cooperation, and the development of specialized tools. Early humans likely targeted large herbivores, such as mammoths, bison, or wild cattle, which provided considerable amounts of meat and fat. Evidence from fossil sites shows patterns of animal bone distribution consistent with coordinated group hunts.

Techniques included ambush hunting, persistence hunting (chasing prey until exhaustion), and driving herds into traps or natural barriers. Projectile points, wooden spears, and cutting implements have been found in association with animal bones, suggesting direct involvement in kills. Distinct methods developed depending on terrain, prey species, and climatic conditions.

Scavenging and Opportunistic Feeding

Not all meat was obtained through active hunting. Early hominins often practiced scavenging—consuming animals that were already dead, usually killed by predators or natural causes. Scavenging provided access to high-energy resources with lower risk than hunting.

Stone tool cut marks overlaying carnivore tooth marks on bones from ancient sites indicate that humans sometimes accessed carcasses after predators. Opportunistic feeding also included targeting animals weakened by disease, age, or injury. These strategies maximized calorie intake and reduced energy expenditure.

Use of Stone Tools and Butchery Marks

The use of flaked stone tools marked a significant technological advancement in meat processing. Early humans used simple flakes, hand axes, and later blades to cut through skin, disarticulate joints, and extract marrow from bones.

Butchery marks—distinctive cuts, chops, and scrape marks—can be identified on excavated animal bones. These marks provide evidence for systematic butchering, skinning, and marrow extraction. Cut mark patterns help researchers understand the sequence of carcass processing and distinguish between activities such as filleting meat and breaking bones for marrow.

Zooarchaeological Record and Animal Carcasses

Zooarchaeologists study animal bone assemblages from ancient sites to reconstruct patterns of human behavior. Excavations reveal details about species hunted or scavenged, the frequency of meat consumption, and seasonality of kills.

Bones with cut marks, percussion fractures, and signs of burning show how carcasses were processed. Changes in bone fragmentation and tool types over time reflect shifts in technology and dietary strategies. Table 1 summarizes examples of evidence commonly found in the zooarchaeological record:

Evidence Type Interpretation Cut marks on bones Butchery for meat removal Percussion fractures Marrow extraction and bone breaking Burned bone fragments Cooking or roasting meat Association with tools Direct processing with stone technology

Adaptations Resulting from Carnivory

Early human consumption of meat shaped a range of biological and behavioral adaptations. These changes influenced not just physical characteristics like brain size and stature but also enabled flexible responses to changing environments and available foods.

Physiological and Metabolic Changes

Carnivory required several key adaptations in the human body. One critical shift was the evolution of a more acidic stomach environment, which helps digest meat and reduces pathogen risks. Human teeth and jaws also changed, with smaller canines and flatter molars that are effective for slicing and chewing both meat and cooked foods.

Meat-eating altered metabolic processes as well. The human digestive tract shortened, reflecting reliance on nutrient-dense animal proteins and fats rather than bulky plant matter. Enzyme production adapted: humans produce less cellulase but more pepsin and other enzymes geared toward protein breakdown.

The ability to process animal fats and proteins efficiently provided consistent energy, supporting survival in diverse habitats. These metabolic adaptations complement other evolutionary shifts linked to carnivory.

Increase in Body Size and Brain Expansion

The introduction of animal foods is closely linked to increases in both body size and brain volume during human evolution. Consuming animal protein provided more calories and essential nutrients like iron, fatty acids, and vitamin B12, supporting growth and development.

Nearly all large-bodied, big-brained hominins—such as Homo erectus and later Homo species—show skeletal evidence of more robust stature than earlier forms. As their diet shifted toward greater meat consumption, brain size expanded substantially.

A larger brain comes with high energy requirements. Meat and marrow, with their concentrated caloric content, helped meet these needs. This change likely supported advanced cognitive abilities, social structures, and tool use, distinguishing humans from other primates.

Dietary Diversity and Human Adaptability

Carnivory did not completely replace plant foods but became one layer of a highly varied diet. Early humans incorporated a broad range of food types, toggling between plant and animal sources as conditions changed. This pattern is one key to human adaptability and survival across continents.

Dietary flexibility allowed hominins to endure climate shifts and off-season scarcity. Skills such as tool use and cooperative hunting increased access to new food sources, including large, fatty animals.

Human adaptability also stems from the ability to exploit different ecological niches, which required cognitive, social, and technological innovations. Dietary diversity remains a defining trait of the species, underpinning long-term evolutionary success.

Comparative Insights From Primates and Modern Humans

Comparisons between the diets of modern humans and their closest living primate relatives shed light on the evolution of meat consumption. Examining what chimpanzees and bonobos eat helps clarify shifts in feeding strategies that distinguish humans.

Chimpanzees and Bonobos: Clues From Closest Relatives

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and bonobos (Pan paniscus) are the closest living relatives of humans. Both species are mostly frugivorous, but chimpanzees supplement their diets with significant amounts of meat from small- to medium-sized mammals, including monkeys and duikers.

Chimpanzee hunts are organized, often involving cooperative group strategies. This behavior offers a glimpse into the selective pressures that might have promoted social cooperation and tool use in early hominins. Bonobos, in contrast, eat meat much less frequently and rely more on fruit, leaves, and small invertebrates.

Meat accounts for only a small proportion of the diet in both species, but the social context is notable. Chimpanzee meat-sharing has been linked to alliance formation and social bonds, suggesting the roots of social meat distribution that later characterized humans.

Contrasts With Modern Human Meat Consumption

Modern humans consume a much greater proportion of meat compared to either chimpanzees or bonobos. Archaeological evidence from hunter-gatherers and Paleolithic sites indicates that meat and animal products have played a key role in the human diet.

Unlike chimpanzees, who hunt small prey occasionally, human hunter-gatherers develop complex hunting tools and strategies to pursue large animals. The acquisition and sharing of meat became central to human social organization and may have influenced evolutionary changes such as increased brain size.

Table 1 compares meat-eating in primates and humans:

Species Frequency of Meat Eating Typical Prey Social Aspects Chimpanzee Occasional Small mammals, monkeys Cooperative hunting Bonobo Rare Small animals, insects Less meat sharing Modern Humans Regular to frequent Large & small animals Complex sharing, trade

The reliance on meat among humans has helped shape cultural norms, nutritional needs, and the structure of prehistoric and modern societies.

Anthropological and Cultural Impacts

The origins of human carnivory profoundly shaped patterns of collaboration, tool use, and cultural innovation. Dietary shifts toward meat influenced not only survival strategies but also the trajectory of human social and technological development.

Collaboration and Social Behavior

Early hominins coordinated group hunts and shared access to large animal carcasses. This level of cooperation is evidenced by archaeological findings of butchery sites showing systematic processing of animal bones.

Group hunting required complex communication and role assignment, laying a foundation for advanced social structures. Through collaboration, individuals could secure more reliable sources of food, which helped stabilize communities.

Shared meals became central to group cohesion. As carnivory intensified, the social bonds around hunting and division of meat contributed to the evolution of extended kin networks and the emergence of communal living arrangements.

Influence on Human Behavior and Technology

The need for efficient meat processing led to advancements in tool technologies. Early stone tools, such as Oldowan and Acheulean hand axes, greatly improved the ability to butcher animals and access nutrient-rich marrow.

Carnivory also spurred cognitive developments. Activities like planning hunts, interpreting animal behavior, and sharing resources encouraged learning and teaching through demonstration, strengthening cultural transmission.

Technical skills expanded alongside changing behaviors. The continuous refinement of hunting tools and techniques illustrates a growing feedback loop between technological innovation and cultural evolution that would persist throughout human history.

Transition to Agriculture

The long dependence on animal protein set precedents for later dietary adaptations. As environmental changes and population growth put pressure on wild game, some groups experimented with plant management and animal domestication.

This transition from hunting and gathering to farming marked a defining shift in human history. Sedentary lifestyles and food storage enabled by agriculture transformed social organization, resource distribution, and eventually led to the rise of complex societies.

Remnants of early carnivory persisted in the ways people balanced hunted and cultivated resources. The integration of meat into agricultural diets influenced nutritional health, economic practices, and the social dynamics of emerging human settlements.

Pioneers and Research in Human Carnivory

The scientific investigation of ancient human diets draws on interdisciplinary research, including archaeological data, fossil records, and studies on dietary evolution. Key figures and research programs have advanced understanding of how and when carnivory emerged among hominins through detailed studies and fieldwork.

Contributions by Paleoanthropologists

Paleoanthropologists have used fossil evidence, cut marks on bones, and isotopic analysis to reconstruct the diets of early humans. By examining animal remains from archaeological sites, researchers have identified tool marks and bone breakage patterns that signal meat consumption and marrow extraction.

Well-known discoveries at sites such as Olduvai Gorge have shown repeated butchery activities by early Homo species. These findings suggest that access to large animal carcasses played a significant role in brain and social evolution.

Analytical techniques, including microscopic wear analysis on teeth and implements, help distinguish between scavenging and active hunting. Through systematic excavation and documentation, paleoanthropologists contribute data that shape our understanding of the shift towards carnivory in the evolutionary record.

The Work of Briana Pobiner and the Human Origins Program

Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist affiliated with the Smithsonian's Human Origins Program, has specialized in researching meat-eating among hominins. Her work involves studying cut-marked bones from African archaeological sites to determine when persistent carnivory first appeared.

Under Pobiner’s direction, the Human Origins Program has gathered and cataloged crucial fossil evidence showing that hominins regularly consumed animal flesh over a million years ago. The program provided logistical and research support for fieldwork at sites in Kenya and beyond, allowing for large-scale analyses.

Pobiner’s research uses experimental butchery and comparative studies to interpret archaeological data and clarify the impact of carnivory on evolutionary changes, such as brain size increase. The work emphasizes rigorous field methods and detailed laboratory analysis to draw reliable conclusions about ancient dietary behaviors.

Synthesis: The Lasting Legacy of Ancient Carnivory

Ancient hominin carnivory played a foundational role in human evolution. Archaeological evidence suggests early humans shifted towards increased meat consumption, which set them apart from other primates. This dietary change brought about adaptations that shaped their biology and behavior.

Key Impacts of Ancient Carnivory:

Aspect Influence of Carnivory Brain Growth Nutrient-rich meat supported larger brain sizes in hominins. Tool Use Hunting and meat processing encouraged the development of tools. Social Dynamics Cooperative hunting fostered complex group interactions. Mobility Meat acquisition shaped migration patterns and territory use.

Charles Darwin recognized the ecological and evolutionary significance of dietary changes. He noted that shifts in food sources could drive anatomical and behavioral adaptations. Ancient carnivory illustrates this, linking dietary evolution to advances in early human survival strategies.

The phrase “meat made us human” refers to the idea that carnivory was crucial in shaping the trajectory of the genus Homo. Consistent access to animal foods influenced not only physical development but also patterns of social cooperation.

As the ecology of early humans changed, so did their relationship with other predators and prey. This relationship affected their evolutionary history, including how they foraged, competed, and adapted to diverse environments.

The legacy of hominin carnivory is still evident in modern human physiology and dietary behaviors. Evolutionary history continues to inform current understanding of nutrition, ecology, and the origins of dietary diversity.