Red Meat and Heart Disease: Examining the Evidence and Myths

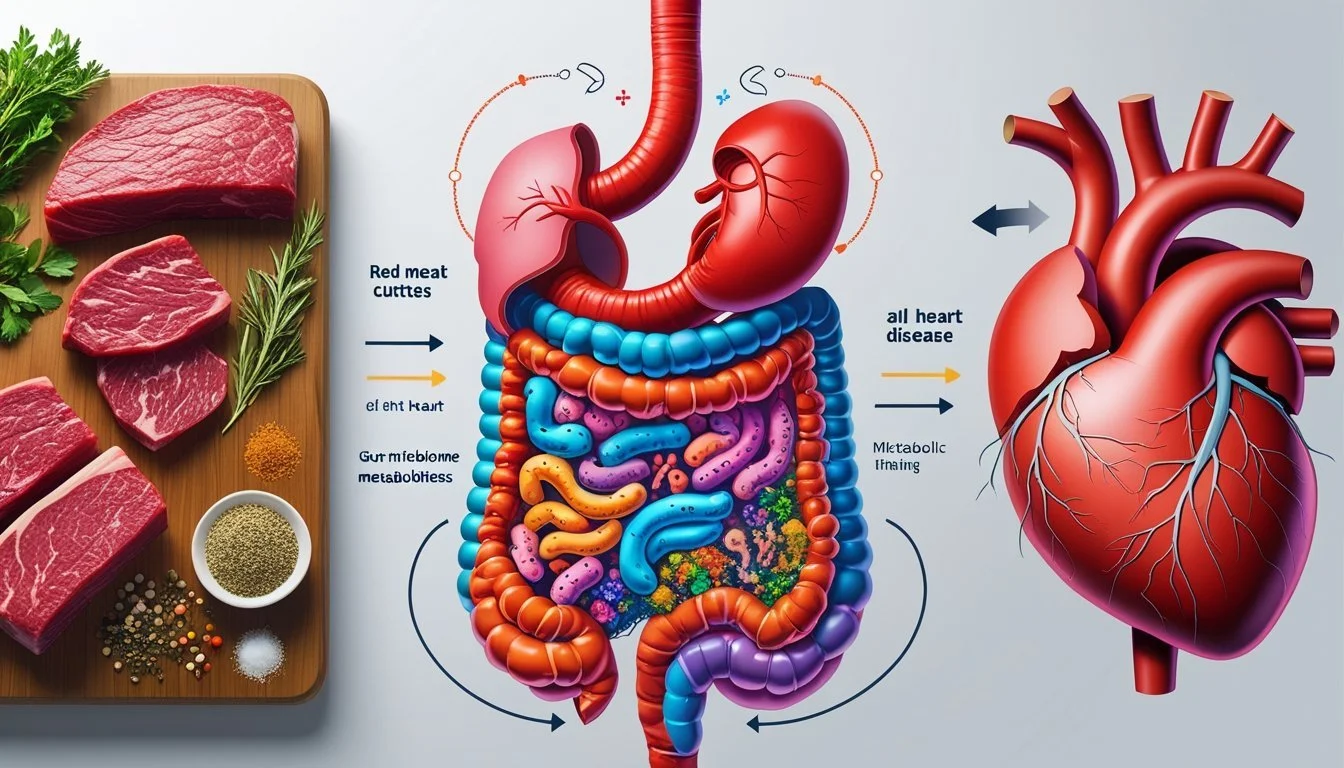

Eating red and processed meat has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, mainly due to factors like saturated fat, cholesterol, and certain chemicals produced in the digestive tract. Multiple studies involving thousands of people have found that higher consumption of beef, pork, and processed meats slightly raises the likelihood of cardiovascular problems, including heart attacks and strokes. These findings have led to ongoing debate about how red meat fits into a heart-healthy diet.

Despite the scientific attention, the relationship between red meat and heart health is more complex than it may first appear. Researchers are examining whether it is the type of meat, the amount consumed, or the way it is processed that matters most. Understanding these factors can help readers make informed decisions about their dietary habits and overall health.

Understanding Red Meat

Red meat includes several types of animal protein such as beef, pork, and lamb. These foods have been part of traditional diets for centuries, but not all red meat is the same, and its impact on health depends on processing, nutrient content, and preparation.

Defining Red Meat Varieties

Red meat refers to meat from mammals that is typically red when raw, distinguishing it from poultry or fish. The most commonly consumed types are beef (from cattle), pork (from pigs), lamb (from sheep), and less frequently, meats like bison and venison.

Beef includes steaks, ground beef, roasts, and organ meats. Pork covers cuts such as chops, loin, and shoulder, as well as specialty products like ham. Lamb is more common in certain regions and has a distinctive flavor. Each type varies in nutrient composition and fat content, which can affect health outcomes.

Within red meats, there is also a distinction between fresh cuts, such as steak or roast, and those subject to preservation methods, such as curing or smoking.

Nutritional Components of Red Meat

Red meat is a rich source of protein, heme iron, zinc, and several B vitamins (especially B12). Heme iron is more easily absorbed by the body than plant-based iron, making red meat a reliable source for individuals at risk of deficiency.

However, red meat typically contains a higher amount of saturated fat compared to other protein sources like poultry or seafood. The fat content is influenced by the animal's cut and how it is prepared. Some lean cuts provide relatively modest fat, while others can be much higher.

A 3-ounce (85-gram) serving of cooked beef or pork provides about 22-26 grams of protein, 2-9 grams of saturated fat (depending on the cut), and 2-3 milligrams of heme iron. These nutrients support muscle maintenance and red blood cell production but elevated saturated fat and frequent intake can raise cholesterol levels.

Unprocessed vs. Processed Red Meats

Unprocessed red meat refers to fresh cuts that have not been cured, smoked, salted, or treated with chemical preservatives. Examples include fresh steak, pork chops, ground beef, or lamb roast.

Processed meats include foods like bacon, sausage, salami, deli ham, hot dogs, and corned beef. Processing methods frequently involve salting, curing, fermenting, or adding preservatives such as nitrates or nitrites.

The nutritional profile of processed meat can differ greatly from unprocessed versions. Processed meats tend to have higher sodium, additional fats, and more additives, which may affect heart health risks. Processed options also often contain higher levels of saturated fat and chemicals formed during processing, some of which have been linked to increased cardiovascular and cancer risks.

Red Meat Consumption and Heart Disease Risk

Multiple studies have found associations between red meat consumption and different forms of heart disease. Research highlights the presence of chemicals, saturated fats, and other factors in red meat that may increase specific cardiovascular risks.

Cardiovascular Disease Associations

Regular consumption of red meat has been linked to an elevated risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (CVD). One key mechanism involves gut bacteria converting nutrients found in red meat into trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), a chemical associated with a higher likelihood of cardiovascular events.

A meta-analysis observed that both unprocessed and processed red meat are correlated with increased rates of heart disease and related health conditions. Processed varieties, such as sausages and deli meats, tend to pose a higher risk due to added sodium and preservatives.

Major contributors include:

Saturated fats found in red meat, which can raise LDL (“bad”) cholesterol.

Inflammation and increased blood sugar, also linked to regular high consumption.

Guidelines in many countries now recommend limiting intake to reduce health risks.

Coronary Heart Disease Risks

Coronary heart disease (CHD) remains one of the most studied outcomes associated with red meat intake. Observational studies have shown that individuals with higher consumption of red and processed meats face a greater risk of CHD and heart attacks compared to those consuming less or choosing plant-based alternatives.

The relationship likely involves a combination of factors:

Higher cholesterol from animal fats,

Elevated TMAO linked to arterial damage,

and inflammatory responses triggered by certain meat components.

For example, data from the UK indicate that if unprocessed red meat consumption was reduced by three-quarters, CHD mortality rates could potentially decrease in the general population.

Heart Failure and Stroke Links

Evidence also connects red meat intake to a higher incidence of heart failure and stroke. Red and especially processed meats contribute to vascular problems both through direct effects on blood vessels and by increasing conditions like hypertension.

Studies consistently show that people eating more red meat have a greater occurrence of both heart failure and different stroke types, particularly ischemic stroke. This risk rises further with large servings and frequent consumption.

Key factors affecting these risks:

Sodium and preservatives in processed meats,

Blood pressure elevation,

Changes in blood lipid profiles.

Reducing red meat intake, especially processed forms, is widely recommended to help lower stroke and heart failure risk.

Evidence from Scientific Studies

Research on red meat and heart disease comes from several major study types. Each provides unique insights into the relationship between meat intake and cardiovascular risk, drawing from direct population data, combined scientific literature, and controlled interventions.

Cohort and Observational Study Findings

Cohort and observational studies have consistently examined large groups over many years.

Many have linked higher intake of red and processed meats to an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). For example, several cohort studies report that people who consume more than one serving of red or processed meat per day face a greater risk of cardiovascular events compared to those with lower intake.

Not all observational results agree, and some differences arise due to adjustments for other risk factors such as body weight, smoking, and physical activity. Some studies detect stronger associations with processed meats than with unprocessed red meats.

Findings often rely on dietary recall questionnaires, which may introduce bias. Still, these studies provide valuable real-world data across diverse populations and time spans.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses combine data from multiple studies to produce broader conclusions. Many such analyses conclude that both red and processed meat consumption are modestly associated with increased risks of CHD and mortality.

A notable meta-analysis published in recent years found that each additional 50 grams per day of processed meat was associated with a significant increase in coronary heart disease risk. When only unprocessed red meat was considered, the association with heart disease was smaller and often not statistically significant.

These reviews typically use strict criteria to select studies and assess quality. They highlight variability among individual study findings but reinforce concerns about processed meat in particular.

Clinical Trials and Their Role

Clinical trials offer controlled environments to assess effects of red meat on cardiovascular biomarkers such as LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and blood pressure.

Results from short-term trials are mixed. Some trials report that lean, unprocessed red meat can be included in a healthy diet without adversely affecting cholesterol or blood pressure, provided overall diet quality is high. Others indicate modest negative effects, especially when higher-fat cuts are used.

There is a shortage of long-term randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on this topic. Existing trials typically focus on surrogate endpoints rather than actual cardiovascular events. While helpful for understanding mechanisms, clinical trials must be interpreted alongside evidence from observational research.

Mechanisms Linking Red Meat to Heart Disease

Research identifies several biological pathways through which the consumption of red meat may increase heart disease risk. These mechanisms focus mainly on nutrient composition and the body's metabolic responses.

Saturated Fats and Cholesterol

Red meat typically contains higher levels of saturated fat compared to poultry or plant-based protein sources. Saturated fat intake is known to raise low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels in the blood, a significant risk factor for atherosclerosis.

Key Points:

Red meat (e.g., beef, pork, lamb): High saturated fat content

LDL cholesterol (“bad cholesterol”): Increases with high saturated fat intake

Atherosclerosis: Formation of fatty plaques in the arteries, promoted by elevated LDL

Blood pressure: May be affected as arteries narrow and stiffen

Multiple studies show that a diet rich in red meat can lead to higher blood cholesterol, which raises the risk for coronary artery disease and related cardiovascular conditions.

Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Red meat consumption may also influence inflammatory and oxidative processes within the body. Compounds produced during digestion, such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), are linked to higher rates of inflammation and atherosclerosis.

Key Points:

TMAO formation: Occurs when gut microbes metabolize nutrients found in red meat

Inflammatory markers: Increase with higher TMAO levels

Oxidative stress: Elevated in diets high in red meat

Blood sugar and vascular health: May be negatively affected by chronic inflammation

Persistent inflammation and oxidative damage promote the buildup of arterial plaque. This process can further elevate cardiovascular risk, particularly when combined with other factors like high cholesterol and elevated blood pressure.

Role of the Gut Microbiome and Metabolites

The relationship between red meat and heart disease is partly influenced by how gut bacteria process components of meat. Chemicals produced by the gut microbiome, including metabolites like TMAO, may have important effects on cardiovascular health.

Gut Bacteria and TMAO Production

When a person eats red meat, certain gut bacteria break down compounds such as choline, lecithin, and carnitine. This process creates trimethylamine (TMA), which is absorbed and converted in the liver to trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO).

TMAO has been linked in studies to a higher risk of atherosclerosis and other heart-related conditions. Research shows that people with higher TMAO levels are more likely to develop plaque in their arteries.

Factors that affect TMAO production include:

Amount and type of red meat consumed

Diversity and composition of the gut microbiome

The body's ability to metabolize TMA

Not all individuals produce TMAO at the same rate, as gut bacteria vary significantly between people. Diet, age, and antibiotic use can also influence TMAO levels.

L-Carnitine and Metabolic Pathways

Red meat is a major source of L-carnitine, a compound important for energy production. Gut microbes metabolize L-carnitine from food, leading to the generation of TMA and, eventually, TMAO.

In this metabolic pathway, L-carnitine serves as a substrate for gut bacteria that are capable of producing TMA. People who eat red meat regularly may have higher populations of these bacteria, which can result in increased TMAO levels.

Table: Key steps in L-carnitine metabolism

Step Description L-carnitine ingestion From beef, pork, and other red meats Gut microbial metabolism Converts L-carnitine to TMA Liver oxidation TMA converted to TMAO

Researchers have found that this process is less pronounced in people who avoid red meat, likely due to differences in gut microbial populations. These observations support the link between red meat, the gut microbiome, and metabolic byproducts that may impact heart disease risk.

Processed Meat Versus Unprocessed Red Meat

Research on red and processed meats shows important differences in health effects, driven largely by how the products are prepared and preserved. These differences have real implications for heart disease risk and overall health.

Differential Health Effects

Processed meats—such as bacon, sausages, and deli meats—consistently show stronger links to heart disease and related conditions compared to unprocessed red meats like beef, pork, or lamb. Multiple studies find that regular consumption of processed meats is associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease and diabetes.

Unprocessed red meats also raise concerns but tend to have a weaker association with cardiovascular risk. For example, increasing unprocessed red meat intake by 50 grams per day is linked to about a 9% higher risk of coronary heart disease, while processed meats pose an even greater risk for the same amount.

Table: Comparison of Health Risks

Type of Meat Heart Disease Risk Diabetes Risk Processed Meats High High Unprocessed Red Meats Moderate Modest

Additives and Preservation Methods

Processed meats contain added preservatives, salt, nitrates, and sometimes sugar. These ingredients are used to extend shelf life and enhance flavor but can increase blood pressure and contribute to plaque buildup in arteries. Nitrates and nitrites may also form potentially harmful compounds during digestion.

Unprocessed red meats do not contain added preservatives or chemical additives, though they are still rich in saturated fat and cholesterol. The absence of additives means unprocessed red meats lack some of the risk factors associated with heart disease found in processed products.

Key Additives in Processed Meats:

Nitrites/nitrates

High sodium

Preservatives

These differences help explain why health organizations recommend minimizing processed meat consumption while still encouraging careful intake of unprocessed red meats.

Dietary Patterns and Heart Health

Dietary patterns are central to understanding how certain foods influence cardiovascular outcomes. Evidence shows that how often a person consumes different types of meat, fish, or plant-based foods can impact their heart health.

Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Benefits

The Mediterranean diet emphasizes fish, poultry, legumes, whole grains, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and olive oil while limiting red and processed meats. Large studies have shown that people following this dietary pattern tend to have lower rates of coronary artery disease and stroke.

This diet provides a mix of nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids from fish, fiber from plant foods, and monounsaturated fats from olive oil. These nutrients help reduce inflammation, improve blood pressure, and support healthy cholesterol levels.

Clinical guidelines often recommend the Mediterranean diet for those at risk of heart disease. It is associated with reduced cardiovascular events, partly due to its limited intake of red meat and preference for white meat and fish. Moderate consumption of eggs is included, though the overall balance leans heavily on plants and seafood.

Comparing Red Meat with White Meat and Fish

Red meat—particularly processed varieties—has been linked to higher cardiovascular risk. Studies indicate that frequent intake of red meat can raise cholesterol, saturated fat, and levels of TMAO, a compound tied to heart disease.

In contrast, white meat like poultry and fish are generally associated with lower cardiovascular risk. Fish, especially fatty varieties like salmon and sardines, provide high levels of omega-3 fatty acids, which help reduce triglycerides and inflammation.

A comparative table:

Food Type Key Nutrients Cardiovascular Risk Indicator Red Meat High in sat. fat, iron Increased risk (when frequent) White Meat Lean protein Neutral or lower risk Fish Omega-3 fatty acids Lowered risk

Choosing poultry or fish instead of red meat aligns with many recommendations for healthier dietary habits and heart health.

Red Meat, Diabetes, and Other Chronic Diseases

Current research evaluates how red meat intake may influence the risk of type 2 diabetes and its links to chronic conditions like kidney disease and obesity. Associations vary based on whether the meat is unprocessed or processed, the amount consumed, and other dietary habits.

Type 2 Diabetes Risks

Multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined the relationship between red meat and type 2 diabetes. Higher consumption of both unprocessed and processed red meat has been associated with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Processed red meats—such as bacon, sausages, and deli meats—tend to show stronger associations with diabetes risk than unprocessed meats. For instance, every additional daily serving of processed meat can increase the risk of type 2 diabetes by 15% to 30%.

Some large genetic (Mendelian randomization) studies have found no clear causal link between red meat and diabetes development. However, dietary patterns high in processed meats consistently correlate with unfavorable metabolic outcomes.

Key factors believed to contribute include sodium, nitrates, and saturated fat content, particularly in processed meats.

Connections with Chronic Kidney Disease and Obesity

Red meat intake has also been studied for its role in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and obesity. Evidence suggests that high consumption of red and processed meat may contribute to obesity, which itself is a significant risk factor for both type 2 diabetes and CKD.

Excess consumption of red meat can increase the renal workload due to its protein content, and some studies have reported a higher risk of CKD among those regularly consuming large amounts of red and processed meats.

For obesity, diets heavy in red and processed meats typically have more calories and saturated fat, both of which are linked with weight gain and increased adiposity. Adopting dietary patterns rich in minimally processed foods, vegetables, and whole grains is associated with a reduced risk of both obesity and related chronic diseases.

Dietary Recommendations and Public Health Guidelines

Dietary guidelines on red meat intake vary, reflecting debates about health risks and scientific evidence. Health organizations recommend practical steps focused on reducing disease risk and supporting long-term heart health.

Guidelines from the American Heart Association

The American Heart Association (AHA) advises limiting red and processed meat to promote cardiovascular health and reduce mortality risk. They highlight the connection between higher consumption of red meat—especially processed varieties—and increased risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.

AHA recommends choosing lean cuts, reading food labels for sodium and saturated fat, and keeping total saturated fat intake to under 6% of daily calories. For reference, their suggestions often include replacing red meat with fish, poultry, legumes, or plant-based proteins.

Evidence points to lower cholesterol and improved blood pressure control when red meat intake is reduced. While some recent studies have questioned the strength of this link, the AHA continues to support moderate to low red meat intake as part of an overall heart-healthy diet.

Balancing Risks and Benefits

Navigating red meat intake involves weighing established health risks against nutritional needs and personal preferences. While red meat is a source of high-quality protein, iron, and zinc, frequent consumption of processed or fatty cuts has been connected to heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and higher mortality in several cohort studies.

Table: Nutrient Comparison (100g servings)

Food Protein (g) Saturated Fat (g) Iron (mg) Beef (lean) 26 2.4 2.6 Chicken (skinless) 27 1.0 1.3 Lentils 9 0.1 3.3

Many guidelines encourage individuals to consider what foods they choose instead of red meat. Replacing some servings with fish or legumes can help reduce saturated fat intake and provide other health benefits. Personal values, individual risk factors, and cultural preferences play a role in finding a sustainable balance.

Lifestyle Factors Influencing Heart Disease Risk

Multiple lifestyle habits play a central role in shaping heart disease risk. Adjustments to physical activity, sleep, body weight, and smoking habits can all have measurable impacts on cardiovascular health.

Physical Activity and Healthy Body Weight

Regular physical activity improves blood circulation, strengthens the heart muscle, and helps control risk factors like blood pressure and cholesterol. It also assists in maintaining or achieving a healthy body weight, which directly reduces cardiovascular strain.

Adults are advised to aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, such as brisk walking or cycling. Even shorter, consistent bouts of movement lead to health benefits. Those who remain inactive face higher rates of heart disease and related complications.

Maintaining a healthy body weight, often defined as a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 24.9, is associated with lower heart disease risk. Excess weight contributes to increased blood pressure, higher levels of LDL cholesterol ("bad" cholesterol), and insulin resistance, all established risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Tracking waist circumference can also help identify risk related to visceral fat.

Sleep and Smoking Cessation

Quality sleep supports blood vessel health, blood pressure regulation, and optimal heart function. Adults typically require 7 to 9 hours of sleep per night. Sleep deprivation or disorders like sleep apnea increase the risk of high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, and arrhythmias.

Smoking is a leading preventable cause of heart disease. Chemicals in tobacco damage blood vessels, raise blood pressure, and accelerate the buildup of plaque in arteries. Quitting smoking significantly reduces risk—benefits appear within weeks of cessation, and continued abstinence further drops risk over time.

Support programs, counseling, and medication can improve cessation success rates. When combined with regular sleep habits, avoiding tobacco use strongly supports better cardiovascular outcomes.

Optimizing Heart Health with Dietary Choices

Choosing the right variety of plant-based foods offers measurable benefits for cardiovascular health. Scientific studies increasingly show that replacing higher-risk foods like red meat with nutrient-rich alternatives supports healthy blood vessels and lowers cardiovascular disease risk.

Incorporating Vegetables, Fruits, and Whole Grains

Eating a range of vegetables and fruits supplies the body with vital nutrients, such as potassium, dietary fiber, antioxidants, and vitamins C and K. These nutrients have demonstrated effects on blood pressure regulation, inflammation reduction, and protection against cellular damage.

Whole grains, including oats, quinoa, brown rice, and barley, provide complex carbohydrates, fiber, and important micronutrients like magnesium and selenium. Their regular consumption is linked to lower total cholesterol and LDL (“bad” cholesterol) levels, both of which are risk factors for heart disease.

Below is a simple table summarizing beneficial options:

Category Examples Key Benefits Vegetables Broccoli, spinach Vitamins, antioxidants, fiber Fruits Berries, oranges Fiber, flavonoids, vitamin C Whole Grains Oats, quinoa, barley Fiber, magnesium, B vitamins

Consistent inclusion of a wide variety from each category maximizes nutrient intake and reduces reliance on less heart-friendly foods.

Legumes and Nuts for Cardiovascular Protection

Legumes—such as beans, lentils, and peas—are high in plant-based protein, soluble fiber, and minerals like potassium and magnesium. Regular consumption has been found to lower cholesterol and stabilize blood sugar, both important for heart protection.

Nuts provide healthy unsaturated fats, plant sterols, and vitamin E. Eating modest amounts (about 1 ounce daily) of nuts such as almonds, walnuts, or pistachios has been shown to lower LDL cholesterol without negatively impacting body weight for most people.

A daily serving of legumes or nuts can often substitute for animal protein at meals, providing comparable satiety and preserving nutrient quality. Combined with vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, legumes and nuts contribute to a comprehensive approach to cardiovascular nutrition.

Current Controversies and Research Gaps

Research on red meat and heart disease is frequently debated due to differing results and scientific approaches. Findings are influenced by industry involvement and distinct methodological choices that affect how risks are evaluated and communicated.

Conflicts of Interest in Nutrition Science

Conflicts of interest are a significant issue in nutrition research, including studies on red meat and heart disease. Funding sources, such as the meat or food industry, can impact study design, reporting, and interpretation of results.

Several reviews have found that industry-funded studies are more likely to report no harm from red meat consumption compared to independent research. Disclosure of financial ties is inconsistent, making it difficult to determine bias.

Researchers and policy makers urge for transparency regarding funding and affiliations. Independent oversight is recommended to reduce any potential bias that may affect study outcomes, particularly regarding risk factors for heart disease linked to red meat.

Limitations in Study Designs

Many studies exploring red meat and cardiovascular risk rely on observational data. These studies can show associations but cannot confirm causation because other lifestyle and dietary factors may play a role.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which are considered the gold standard, are rare in nutrition due to practical and ethical limits. As a result, most available research cannot isolate the specific effects of red meat from confounding variables, such as overall diet quality, exercise, or socioeconomic status.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews point out that inconsistent definitions and self-reported dietary data reduce reliability. Variability in study design, population, and length of follow-up further complicate the understanding of the relationship between red meat and heart disease.