How Freeze-Thaw Cycles Ruin Food Faster and Compromise Quality

Freeze-thaw cycles quickly damage frozen food by causing ice crystals to expand and contract, rupturing cell walls and degrading texture, taste, and nutritional quality. Each time food undergoes a freeze and thaw, the structural integrity is weakened, resulting in noticeable moisture loss, mushy consistency, and even flavor changes.

These recurring temperature changes are common in frost-free freezers and during poor storage practices, leading to additional loss of quality and increased risk of bacteria growth if not managed carefully. Understanding the process and its effects helps consumers keep their frozen foods safer and better tasting for longer.

Understanding Freeze-Thaw Cycles

Freeze-thaw cycles involve repeated freezing and thawing of water-rich substances, affecting both the structure and quality of foods. These cycles are especially relevant to frozen foods, where phase transitions play a key role in determining shelf life and texture.

Defining Freeze-Thaw Cycles

A freeze-thaw cycle occurs when the temperature of a substance drops below the freezing point (32°F or 0°C), causing water inside it to freeze into ice. When temperatures rise above freezing again, the ice melts, returning the water to its liquid state.

Each time food passes through this cycle, it undergoes physical changes. Repeated freeze-thaw exposure is common in frozen storage environments where temperature control fluctuates.

It is important to note that freeze-thaw cycles are counted based on the number of times the temperature crosses the freezing threshold—each crossing represents a complete cycle. Foods with higher moisture are more susceptible because the water content readily freezes and thaws.

The Science Behind Freezing and Thawing

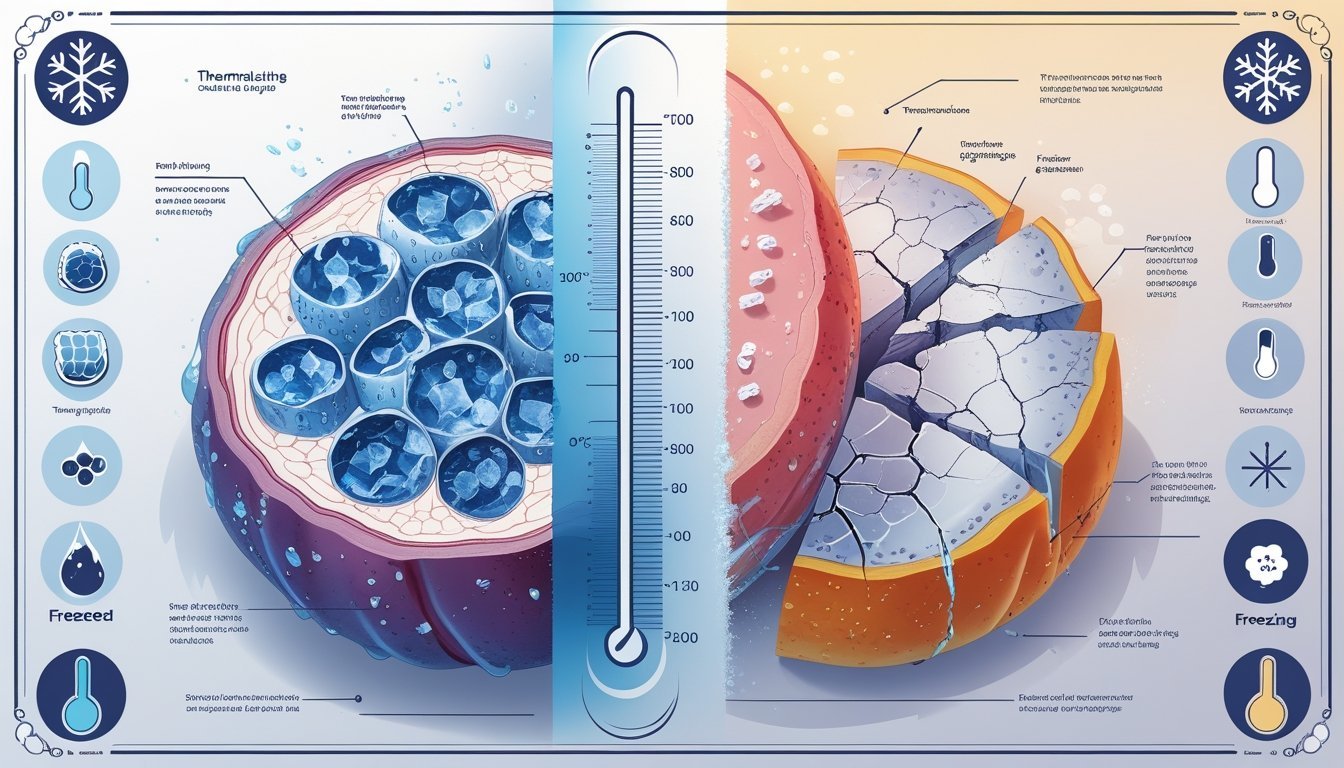

When food freezes, water inside shifts from a liquid to a solid phase, expanding in volume and forming ice crystals. The formation and growth of these crystals often disrupt cell walls and alter food texture.

Rapid freezing results in smaller crystals, causing less damage. Slow freezing forms larger crystals, which are more likely to rupture cell membranes and result in moisture loss when food thaws.

Phase transition—the change between solid and liquid states—is central to this process. The stability of food during frozen storage depends on minimizing the occurrence and duration of these transitions.

Why Cycles Occur in Food Storage

Variation in storage temperatures is the main driver of repeated freeze-thaw cycles in frozen foods. Freezers that are frequently opened, have inconsistent performance, or experience power interruptions allow foods to dip above and below the freezing point.

Improper packaging can also contribute, as it may allow localized warming or exposure to air. This inconsistency leads food to undergo multiple freeze-thaw cycles during storage or transport.

These cycles increase the risk of quality deterioration, as each passage causes potential structural and chemical damage. Controlling both temperature and storage conditions is essential to limit cycle frequency and preserve food integrity.

How Freeze-Thaw Cycles Damage Food

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles degrade food quality by altering structure, distributing water unevenly, and causing loss of moisture. These processes result in changes to texture, taste, and appearance that are usually irreversible and detrimental.

Structural Changes and Ice Crystal Formation

During freezing, water in food forms ice crystals. If freezing happens slowly, these crystals grow large and can pierce cell walls and membranes. Upon thawing, this physical damage becomes evident as soft, mushy textures or visible tears in structure.

A single freeze-thaw cycle already causes some harm, but repeated cycles accelerate crystal growth through ice recrystallization. As water repeatedly freezes and thaws, ice crystals merge and become larger, leading to greater cellular rupture and further structural breakdown. Modified crystal morphology after multiple cycles often means food loses its original firmness and quality, particularly in fruits, vegetables, and meats.

Notably, careful freezing with rapid temperature drops can minimize initial crystal size, but once food is subjected to fluctuating temperatures, control over crystal development is lost. This is why repeated cycles are especially problematic in home freezers and during transport interruptions.

Moisture Loss and Drip Loss

The breakdown of cell structure caused by ice crystals releases water formerly held within cells. When food thaws, this water escapes as "drip loss," and is visible as liquid in packaging or on plates. Key nutrients can be lost with this moisture, compounding the reduction in food quality.

Moisture migration continues throughout each cycle as water redistributes from the inside of cells to intercellular spaces and then to the surface. Items like meat, fish, fruits, and vegetables show higher drip loss with each additional cycle. Visual cues include pools of liquid, a drier appearance in the food, and less juiciness after preparation.

Drip loss is especially concerning for texture-sensitive products like berries and seafood. Even a single freeze-thaw cycle can cause visible damage, but repeated cycles speed up the deterioration and nutrient loss.

Impact on Water Holding Capacity

The ability of food to retain water, called water holding capacity, is closely tied to its structure. Damage to cell walls and membranes during freeze-thaw cycles leaves food unable to keep moisture bound inside.

Proteins in meats and cellular networks in fruits or vegetables are altered, leading to increased exudation (fluid seepage) during thawing and cooking. Studies show that repeated cycles result in greater loss of water, which also affects weight, market value, and mouthfeel.

This loss in water holding capacity changes how food cooks and feels. Meats may become tough and dry, vegetables soft and soggy, and baked goods crumbly. Table 1 shows typical water holding capacity loss in common foods after repeated freeze-thaw cycles:

Food Type % Water Holding Loss (After 3 Cycles) Pork Patty 12–18% Berries 14–20% White Fish 10–16%

Effects on Food Quality and Sensory Properties

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles can degrade frozen food by impacting texture, color, appearance, flavor, and aroma. Each of these sensory and quality characteristics is affected in different ways depending on the food type and storage conditions.

Texture: Tenderness and Juiciness

Freeze-thaw cycles disrupt the structure of muscle fibers and plant cell walls due to the formation and melting of ice crystals. As ice crystals grow during freezing, they puncture cell membranes. When thawed, this damaged tissue loses more water, resulting in increased drip loss.

Meat loses its tenderness and juiciness after several freeze-thaw cycles. Studies show quality deterioration, especially in ground or quick-frozen meat products, making them less appealing to consumers. Bread and produce may become soggy or mushy, reflecting cell structure breakdown.

Loss of water not only affects mouthfeel but also impacts the ability of foods to retain seasoning and marinades. The table below summarizes typical texture changes:

Food Type Texture Change Meat Dry, tough, crumbly Fish Soft, watery Vegetables Mushy, limp

Color and Appearance Changes

Color changes indicate underlying chemical or physical quality loss. Freeze-thaw cycles often result in color fading, browning, or darkening due to pigment breakdown and oxidation.

For meat, repeated cycles can cause myoglobin oxidation, turning red cuts brown or gray. Produce might lose brightness, making vegetables and fruits look dull or blotchy. Surface moisture loss during thawing can cause freezer burn, leading to rough texture and uneven color patches.

Color alterations can make food less attractive, reducing consumer acceptance even before tasting. This impacts overall visual appeal and perceived freshness on shelves or after reheating.

Flavor, Odor, and Taste Alterations

Food compounds responsible for characteristic flavors and odors are affected by repeated freeze-thaw cycles. As cell structures rupture, volatile flavor compounds may escape or react with oxygen, resulting in stale or off odors.

Meats often develop undesirable tastes described as rancid or metallic due to lipid oxidation. Vegetables and fruits may lose sweetness and gain bitterness. Freezer burn further imparts a bland taste and unpleasant smell.

Sensory panels frequently report diminished flavor and aroma intensity in products that have undergone multiple freeze-thaw cycles, confirming the challenges in maintaining food's sensory quality after repeated handling.

Physicochemical and Microbiological Impacts

Freeze-thaw cycles can alter both the chemical structure and safety of foods. Shifts in protein conformation, breakdown of fats, and changes in water compartmentalization often create an environment more favorable for both chemical damage and microbial spoilage.

Protein Denaturation and Lipid Oxidation

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles destabilize protein structures within food. This denaturation often results in a loss of water-holding capacity, resulting in drier and tougher textures after thawing.

Lipid oxidation is accelerated by the disruption of cell membranes and exposure of unsaturated fats to oxygen. This process triggers the formation of compounds measured by TBARS (thiobarbituric acid reactive substances), which can cause off-flavors and reduce nutritional value. Even a single freeze-thaw event can increase these unwanted chemical reactions.

Both protein denaturation and lipid oxidation can lower taste and nutritional quality, while encouraging texture breakdown. Fatty foods such as meats or baked goods are especially at risk.

Changes in pH and Water Activity

The process of freezing and thawing causes cellular damage, leading to leakage of cell contents and shifts in the local pH of foods. Lowering or raising pH can affect both flavor and shelf life, sometimes accelerating spoilage reactions.

Water activity (aw) also changes as ice forms and melts. During thawing, concentrated areas of unfrozen water allow for increased enzymatic activity and chemical reactions. This can further deteriorate food structure and create favorable conditions for microorganisms.

Drip loss—free water escaping from the cellular matrix—can increase moisture availability on the surface, compounding these effects. Foods become more vulnerable to spoilage as both pH and water activity fluctuate.

Microbial Growth and Spoilage

Freezing slows but does not eliminate all microbial activity. When food is thawed, any surviving bacterial or fungal cells can rapidly resume growth, particularly in areas with elevated water activity.

Repeat freeze-thaw cycles can create microenvironments with damaged tissue and higher pH, supporting the growth of spoilage organisms. Listeria monocytogenes and other psychrotrophic pathogens are especially concerning, as they can multiply at refrigerator temperatures.

As spoilage microbes proliferate, signs such as off-odors, discoloration, and textural changes become evident. Vigilance is essential, as thawed foods spoil much faster and present higher safety risks if not consumed promptly.

Food Categories Affected by Freeze-Thaw Cycles

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles harm both the texture and safety of many foods, affecting their taste, nutritional value, and shelf life. Understanding which categories are most vulnerable allows for better storage and less waste.

Meat and Poultry

Meat and poultry are highly sensitive to freeze-thaw cycles. Repeated freezing and thawing causes moisture loss, leading to drier, tougher products.

Muscle fibers in beef, chicken, and pork become damaged as ice crystals form and melt, promoting further protein breakdown. This process decreases meat quality, results in a loss of juiciness, and can make the appearance unappealing.

Surface dehydration, known as freezer burn, is common, especially in unwrapped or poorly wrapped items. Studies show that after around three cycles, both flavor and texture may deteriorate to the point that the food is no longer acceptable for consumption.

Seafood and Aquatic Products

Seafood, including fish and shellfish, is particularly vulnerable due to its delicate texture and higher water content. Freeze-thaw cycles in aquatic products can lead to extensive moisture loss and changes in protein structure.

These changes cause softening and mushiness, reducing consumer appeal. Nutritional value may decrease due to oxidation of proteins and lipids, affecting omega-3 fatty acids commonly found in fish.

Repeated cycles may also increase drip loss after cooking or thawing, further reducing yield and palatability. This makes consistency and safety harder to maintain, especially in perishable food products like shrimp or salmon.

Fruits and Vegetables

Fruits and vegetables experience significant cell damage when exposed to multiple freeze-thaw cycles. The water inside their cells expands as it freezes, rupturing cell walls and causing a soggy or mushy texture after thawing.

Vegetables with a high water content, like tomatoes and cucumbers, are most affected, while root vegetables and those with thicker cell walls may show less damage but still lose crispness.

Nutrient loss, particularly of vitamins C and B, is possible when juices and cellular fluids leak out during thawing. This affects not only taste and appearance but also nutritional value.

Dairy and Ice Cream

Dairy products such as cheese, yogurt, and milk suffer from separation and texture changes during freeze-thaw cycles. Ice cream is specifically susceptible to ice crystal growth, which can make the product gritty and reduce creaminess.

Repeated temperature changes break down fat globules and proteins, leading to water separation and a loss of smooth mouthfeel. In some cheeses, this process leads to crumbling and increased spoilage risk.

Frozen foods containing dairy ingredients may also become unpalatable, with off-flavors and visible texture breakdown occurring after only one or two cycles.

Freeze-Thaw Cycles and Food Shelf Life

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles significantly shorten the shelf life of frozen foods by degrading quality and increasing risks of spoilage. These cycles also affect safety through accelerated chemical changes and potential microbial growth.

Impact on Shelf Life and Quality Maintenance

Each freeze-thaw cycle puts stress on food, causing ice crystals to grow and rupture cell walls. This often leads to moisture loss and changes in texture, directly reducing shelf-life. For example, foods subjected to multiple freeze-thaw events typically show decreased water-holding capacity and increased cooking or thaw loss.

Key quality parameters—such as flavor, appearance, and nutritional value—can also decline after repeated cycles. Protein and lipid oxidation increase after each cycle, creating off-flavors and reducing the overall acceptability of the food. In seafood and meats, structural breakdown is common, leading to mushy or dry products.

To preserve quality, maintaining a consistent frozen state is recommended, as fluctuations in temperature disrupt food structure. Antifreeze proteins and stabilizers can help in some cases, but even these additives have limits.

Indicators of Spoilage and Safety Concerns

Visible changes like discoloration, liquid pooling, or freezer burn often signal spoilage after multiple thawing events. Increased thaw loss can be seen as excess water or drips when defrosting. These are strong indicators that shelf-life has already been compromised.

Chemical markers such as rising pH, increased TBARS (a marker of fat oxidation), and higher protein carbonyl content point to invisible deterioration. Spoilage bacteria and pathogens can multiply rapidly if food is held at unsafe temperatures between freeze-thaw cycles.

Safety becomes a concern since the quality loss may not always be obvious. Eating food that has repeatedly thawed and refrozen may increase the risk of foodborne illness, especially in high-protein foods like meat or seafood. Always check texture, smell, and any signs of spoilage before consumption.

Mitigating Freeze-Thaw Damage in Food

Frequent freeze-thaw cycles can damage food structure and quality, but several strategies can minimize these harmful effects. Addressing both handling techniques and advances in food science helps preserve texture, flavor, and nutrition.

Proper Freezing and Thawing Techniques

The use of rapid freezing is critical because it forms smaller ice crystals within food tissues. These smaller crystals cause less cellular damage compared to slow freezing, which allows large ice crystals to form and disrupt cell walls.

To maintain food safety and quality, thaw food slowly in the refrigerator or use cold water in a sealed bag to prevent contamination. Quick thawing at room temperature increases risk of spoilage and microbial growth.

Avoid refreezing food that has completely thawed, as multiple freeze-thaw cycles increase moisture loss and degrade both texture and flavor. According to research, spoilage rates climb with longer post-freezing thaw periods.

Key Guidelines for Minimizing Damage:

Freeze food quickly with blast freezers or at temperatures below -18°C.

Thaw food in cold conditions.

Limit the number of freeze-thaw cycles.

Use of Cryoprotectants and Antifreeze Proteins

Cryoprotectants are substances added to food to protect against freeze-thaw damage by reducing ice crystal growth. Examples include sugars (like sucrose), salts, polyols, and some proteins.

Antifreeze proteins (AFPs), also known as ice binding proteins or antifreeze peptides, work by binding to ice crystals and inhibiting their growth through a mechanism called thermal hysteresis capacity. This stops ice recrystallization, which normally ruins food texture.

In the food industry, AFPs are sourced from plants, fish, and insects and can be used in products such as ice cream, frozen dough, and seafood. When hydrocolloids like guar gum or carboxymethylcellulose are added, they also help stabilize ice and reduce texture changes.

Cryoprotective Solutions Cryoprotective Effect Sugars, Polyols, Salts Reduce cell damage, limit ice growth Antifreeze Proteins/Peptides Inhibit ice recrystallization, maintain texture Hydrocolloids Control ice crystal structure, stabilize frozen foods

Using these methods helps extend shelf life and maintain food quality during frozen storage.

Role of Environmental and Processing Factors

The rate at which freeze-thaw cycles degrade food depends on both how food is stored and on specific food additives or ingredients. Factors like humidity, temperature variation, and type of substances added can alter the extent of damage during repeated freezing and thawing.

Frozen Storage Conditions

Frozen storage conditions such as temperature stability, humidity, and airflow play central roles in food quality during freeze-thaw cycles. Fluctuations in temperature promote larger ice crystal growth, which ruptures cell walls and leads to moisture loss and texture degradation in meat, fruits, and vegetables.

High humidity inside storage units can further encourage water migration within the food. This tends to result in drip loss, where nutrients and flavor compounds are carried away with the melting ice upon thawing. Air circulation, if too strong or uneven, can cause surface dehydration and increase the risk of freezer burn.

The total moisture content of the food also affects the extent of damage. Products with higher water content experience more pronounced cell rupture and loss of juiciness. Maintaining a steady low temperature and limiting freeze-thaw cycles are key for preserving structural integrity and minimizing quality loss.

Effects of Salt, Sucrose, and Biopolymers

Salt and sucrose are common additives that influence how water freezes in food. Both can lower the freezing point, reducing the amount of freezable water and limiting the formation of large damaging ice crystals. This can help preserve food texture, especially in processed meats and some bakery items.

However, salt can also accelerate protein denaturation during a freeze-thaw cycle. This leads to a drop in solubility and impaired gel formation in products such as fish or meat (Yu et al., 2024). Sucrose, while protective in moderate amounts, may cause excessive sweetness or affect water migration if concentrations are too high.

Biopolymers—such as carrageenan, gelatin, and alginate—are often used to bind moisture and stabilize food structure during freezing. They help reduce syneresis (water loss) and maintain texture upon thawing. These additives are particularly beneficial in frozen desserts and ready meals, where repeated freeze-thaw cycles are likely.

Advancements in Freeze-Thaw Cycle Research

Freeze-thaw cycles present persistent challenges for preserving food quality, leading to damaged textures and nutrient loss. Several scientific and technological breakthroughs are reshaping how foods are protected at subfreezing temperatures.

High-Pressure Freezing and New Technologies

High-pressure freezing (HPF) is being applied to food preservation to control ice formation and protect cellular structures. This technology reduces the size and quantity of ice crystals, preventing severe cell rupture and water loss. HPF can thaw food more rapidly at lower temperatures, but differences in texture and color can occur, depending on the food matrix and pressure applied.

Other new technologies include using antifreeze proteins and recombinant proteins to inhibit ice crystal growth during both freezing and thawing processes. These proteins act at the microscopic level, limiting damage to cell membranes. The development of non-toxic cryoprotectants such as glycerol offers further improvements without compromising food safety.

Applications of Machine Learning and Chemical Synthesis

Machine learning models now analyze large datasets to identify optimal freezing and thawing parameters for various foods. This approach helps minimize freeze-thaw damage by predicting changes in water content, glass transition temperature, and textural properties. Automation using these models streamlines industrial freezing cycles, ensuring more precise and consistent outcomes.

Chemical synthesis plays a role in developing new cryoprotectants and glass-forming agents that can lower the glass transition temperature. Scientists are able to design food-safe, non-toxic additives that protect cellular integrity during deep freezing. Tables of data generated by these models guide recipe formulations and storage protocols.

Future Trends in Food Cryopreservation

Future advances focus on further reducing freeze-thaw cycle damage by combining physical, chemical, and computational strategies. Research into glass transition and vitrification aims to create stable, amorphous food matrices with minimal ice crystal formation.

Emerging trends also include the synthesis and large-scale production of recombinant proteins that act as potent antifreeze agents. As regulations tighten, non-toxic alternatives to traditional cryoprotectants such as glycerol become critical for consumer safety. The continued integration of machine learning will help optimize preservation conditions for a wider range of foods.

Thermal and Physical Properties Related to Freeze-Thaw Cycles

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles change the way heat and moisture move through food, which impacts both texture and quality. Key thermal properties like conductivity and mechanisms like conduction and convection determine how food responds to temperature changes.

Heat and Mass Transfer in Frozen Foods

When food undergoes freezing, water turns into ice, altering its structure. During thawing, ice melts and moisture can migrate, causing cell walls to rupture. This movement of heat and mass affects moisture loss and can speed up spoilage.

Freeze-thaw cycles increase the rate at which fluids are redistributed inside the food. This can cause a breakdown in structure, resulting in drip loss and changes in texture. Moisture migration is a primary reason for quality loss in frozen foods.

Some food components, such as proteins and starches, can be denatured or altered during these cycles. This effect is more pronounced with repeated cycles, as both water and solutes shift location with each freezing and thawing process.

Thermal Conductivity, Conduction, and Convection

The thermal conductivity of food determines how quickly it freezes or thaws. Foods with high water content transmit heat faster, but ice has lower conductivity than liquid water, leading to uneven temperature distribution during freezing and thawing.

Conduction is the direct transfer of heat through food materials. Denser foods with more uniform structure often conduct heat more evenly, minimizing localized thawing. In contrast, porous or aerated foods may experience uneven thawing and freezing.

Convection can also play a role, especially when foods are surrounded by air or liquid during freezing or thawing. Air movement across the surface can speed up temperature changes, while stagnant conditions can slow the process and cause temperature gradients within the food mass.