Substituting for Alkalinity and Acidity in Complex Recipes

Effective Ingredient Alternatives and Tips

Balancing acidity and alkalinity is essential for achieving the right flavor and structure in complex recipes. Swapping acidic or alkaline ingredients can help adjust taste, texture, and even the appearance of a dish without sacrificing overall quality. Knowing which substitutions work best—like using baking soda to neutralize excessive acidity or selecting low-acid alternatives for sensitive palates—empowers cooks to fine-tune recipes and adapt to dietary needs.

Readers looking to create harmonious meals or troubleshoot recipes that turned out too sharp or flat will find practical solutions here. Gradually transitioning to non-acidic or more alkaline ingredients can help ease the palate while maintaining flavor and integrity, making each dish both enjoyable and approachable.

Understanding Alkalinity and Acidity in Recipes

Acidity and alkalinity are fundamental to how ingredients interact, impact flavor profiles, and influence the cooking process. Knowing how to recognize and adjust these properties is key to achieving balanced results in recipes.

Defining Acidity and Alkalinity in Food

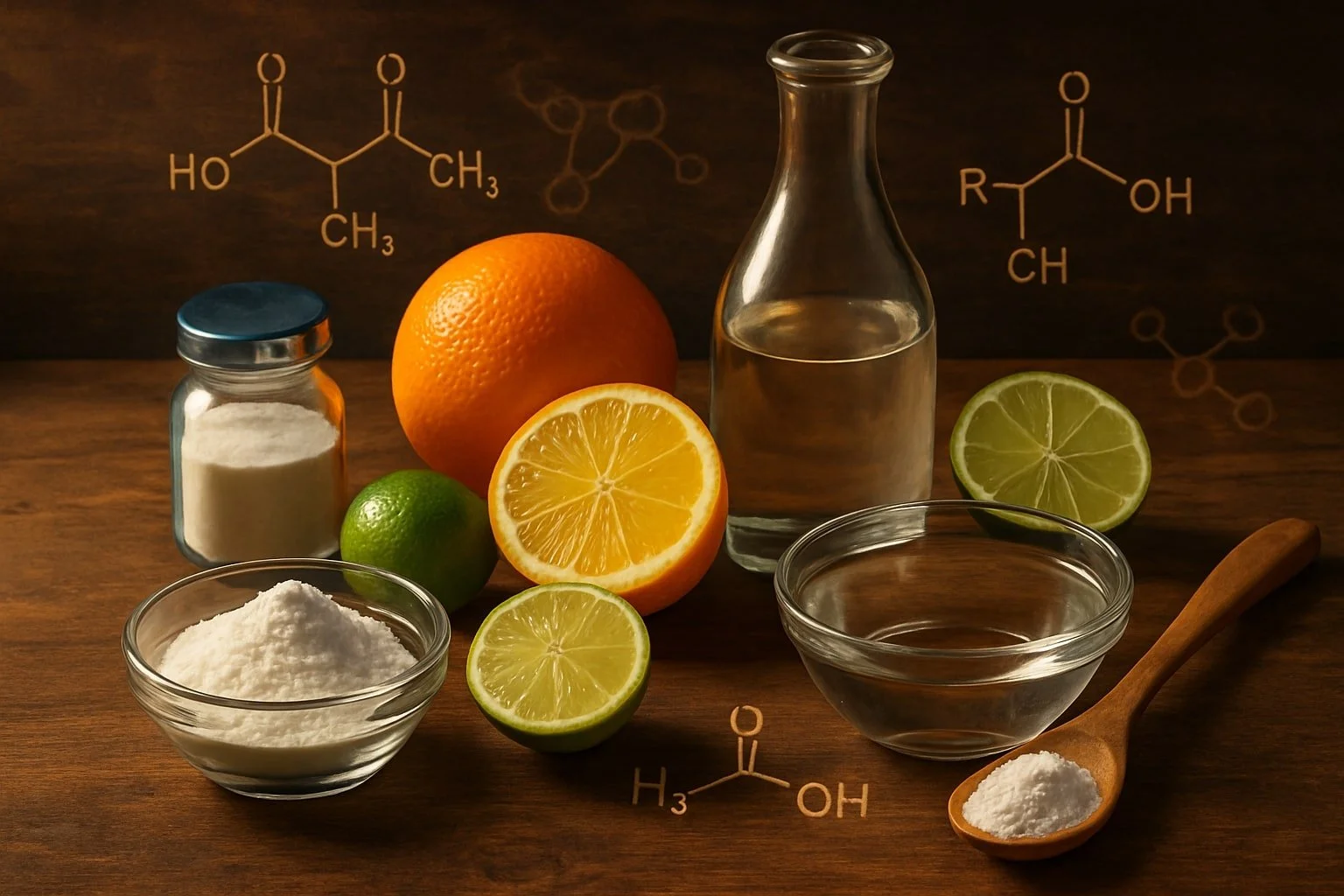

Acidity and alkalinity measure the concentration of hydrogen ions in food, indicated by the pH scale ranging from 0 (most acidic) to 14 (most alkaline). Most foods fall somewhere between these extremes, affecting both their flavor and chemical behavior in cooking.

Acidic foods, such as citrus, vinegar, and tomatoes, contribute sour or tangy notes and often preserve color or texture. Alkaline foods, like baking soda and certain leafy greens, create a milder, sometimes bitter taste and play a role in chemical leavening.

Understanding which foods are acidic or alkaline helps cooks identify potential substitutions or anticipate changes in flavor and reaction. This foundational knowledge is essential for working with complex recipes where multiple reactions occur at once.

The Role of pH in Cooking

The pH level in ingredients directly influences not only taste but also texture, browning, and shelf life. For example, acidic environments can prevent enzymatic browning in fruits and vegetables, while alkaline conditions enhance the Maillard reaction, deepening browning in baked goods.

Table: Effects of pH on Cooking

pH Level Effect on Food Low (acidic) Tangy flavor, preserves color Neutral (7) Mild flavor, stable textures High (alkaline) Softer texture, more browning

The interaction between acidic and alkaline ingredients also determines how baking agents—like baking soda or powder—produce gas bubbles for leavening. Recognizing this can prevent texture problems or flavor imbalances when substituting ingredients.

Balancing Flavors and Taste

Maintaining the right balance between acidity and alkalinity is essential for achieving harmonious flavor profiles. Too much acidity can overwhelm a dish, causing it to taste sharp or harsh, while excessive alkalinity may leave a soapy or bland aftertaste.

Chefs often use acids—such as a squeeze of lemon juice or a splash of vinegar—to brighten heavy or fatty dishes. At the same time, a touch of baking soda can mellow overly acidic sauces and soups.

Common Flavor Balancing Tips:

Add acids to light, freshen, or counteract excessive sweetness.

Use alkaline agents for mellowing acids or encouraging browning.

Taste and adjust incrementally to avoid overpowering flavors.

Understanding these adjustments lets cooks tailor recipes to personal preferences or ingredient availability while preserving the intended flavor and texture.

Common Alkaline and Acidic Ingredients in Cooking

Acidity and alkalinity play crucial roles in both flavor and function in complex recipes. Choosing the right acidic or alkaline ingredient can significantly affect taste, texture, and even color in dishes.

Types of Acidic Ingredients

Acidic ingredients lower the pH of foods and are essential for both flavor development and chemical reactions in recipes. Common examples include vinegar, lemon juice, buttermilk, sour cream, yogurt, and cream of tartar.

These acids can brighten flavors and provide tanginess. They also influence the texture of baked goods by tenderizing gluten. For example, buttermilk in pancakes ensures a soft crumb, while yogurt gives a pleasant sour note.

Citrus juices and vinegars are often used to balance sweetness or saltiness. Cream of tartar, a powdered acid, is frequently added to stabilize egg whites and prevent sugar syrups from crystallizing. These ingredients are chosen carefully to complement and not overpower other flavors.

Ingredient Typical Use pH Range Vinegar Pickling, salad dressing 2-3 Lemon juice Marinades, baked goods 2-3 Buttermilk Baking, pancakes 4.4-4.8 Yogurt Baked goods, sauces 4-5 Cream of tartar Meringues, syrups, baking ~3.5

Types of Alkaline Ingredients

Alkaline ingredients (also called basic ingredients) raise the pH in recipes and can help to neutralize acids. The most common alkaline ingredient in cooking is baking soda (sodium bicarbonate).

Baking soda is popular in baked goods because it helps them rise and enhances browning by increasing alkalinity. Other alkaline substances include baking powder (which contains both an acid and a base) and certain mineral waters.

Alkalinity can dramatically affect both texture and flavor. For instance, using baking soda in cookies creates a crisp exterior and a rich golden color. Certain vegetables, such as brussels sprouts and some melons, are naturally alkaline, though less commonly used purely for their pH effects.

Ingredient Typical Use pH Range Baking soda Baking, tenderizing ~8-9 Baking powder Baking (with acid + base) ~7-8 Mineral water Breading, some batters 7-8.5

Leavening Agents and pH

Leavening agents are substances that cause doughs and batters to rise by producing gases. Their effectiveness is closely tied to the pH of the mixture.

Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) needs an acidic ingredient to react and produce carbon dioxide for leavening. In recipes lacking acids, it may leave a soapy taste and excess alkalinity. In contrast, baking powder contains both an acid and a base, allowing consistent leavening without needing extra acidic ingredients.

Cream of tartar is commonly paired with baking soda to create homemade baking powder or to stabilize whipped egg whites. The choice between baking powder and baking soda depends on the recipe's overall acidity or alkalinity. Proper balance ensures optimal rise, taste, and texture.

Principles of Substituting for Alkalinity and Acidity

Swapping acidic or alkaline ingredients in complex recipes requires understanding how these components influence taste, structure, and nutrient availability. Each substitution decision can affect the final food in multiple ways, beyond simply matching pH or sourness.

Why Substitute: Flavor, Texture, and Nutrition

Cooks and bakers substitute acidic or alkaline ingredients to alter recipes for dietary preferences, available ingredients, or desired outcomes. For example, using yogurt instead of buttermilk in pancakes introduces similar acidity but a thicker texture and slightly tangier flavor.

Alkaline ingredients like baking soda impact browning and leavening, while acidic substances such as lemon juice or vinegar can brighten flavors and tenderize proteins. Replacing one with another may shift food taste, alter rise, or affect how dough develops.

Nutritional considerations also play a role. Some substitutes may add or remove essential nutrients. Swapping cultured dairy for plant-based alternatives may change vitamin, mineral, and fat profiles. Ingredient substitutions should be carefully selected to preserve both texture and nutritional balance.

Assessing Ingredient Functions

Examining what each ingredient does is crucial for successful substitution. Acidic agents might balance sweetness, activate leavening, or provide tart undertones, as seen when using cream of tartar to stabilize egg whites or when yogurt reacts with baking soda in quick breads.

Alkaline ingredients often help doughs rise or create characteristic textures, such as when baking soda is used in cookies to enhance spread and browning. Substituting for alkalinity without considering the mechanism—like using baking powder (which contains both acid and alkali) rather than baking soda—can result in a dense or bitter product.

It’s important to match not just the chemical reaction but also the intensity and use. For example:

Ingredient Function Typical Substitutions Baking Soda Leavening, browning Baking powder + acid Buttermilk Acidity, flavor Yogurt, milk + vinegar Lemon juice Acidity, flavor Vinegar, citric acid

Understanding Flavor Profiles When Substituting

Flavors introduced by acidic or alkaline replacements influence the character of the dish. Using vinegar instead of lemon juice imparts a sharper sourness, while substituting cocoa processed with alkali (Dutch-process) instead of natural cocoa changes both color and bitterness.

Food taste can be enhanced or muted depending on the source of alkalinity or acidity. Common substitutions such as using apple cider vinegar in salad dressings where white vinegar was called for can slightly sweeten or mellow the finish, affecting the dish’s balance.

Testing and tasting remain key, as some substitutes bring underlying flavors that may clash or harmonize differently. Understanding each ingredient’s flavor profile ensures that changes enhance the final dish’s taste rather than overwhelm it.

Substituting Acidic Ingredients in Complex Recipes

Acidic ingredients play a key role in recipes by balancing flavors, aiding in chemical reactions, and contributing to texture. Substituting them requires careful attention to both taste and function to maintain the integrity of the dish.

Acidic Substitutes: Lemon Juice, Vinegar, and More

When a recipe calls for an acidic ingredient, common substitutes include lemon juice, vinegar (such as white, apple cider, or wine vinegar), and lime juice. These all provide similar acidic profiles, but each brings distinct flavors and intensities. For recipes needing a gentler acidity, orange juice offers a milder taste.

Dairy-based options such as yogurt, sour cream, and buttermilk introduce acidity while also adding creaminess, making them suitable for baking, salad dressings, and marinades. In savory dishes, a splash of white wine or a pinch of parmesan cheese can supply brightness and depth. If acidity is not only for flavor but also for activating baking soda, be sure the substitute has a similar pH level.

A quick reference table:

Ingredient Substitutes Lemon juice Vinegar, lime juice, orange juice Vinegar Lemon juice, white wine Buttermilk Yogurt + milk, milk + vinegar

Choosing the Right Substitute for Flavor

Each substitute changes the character of a dish. Lemon juice is sharp and citrusy, while vinegar has a sharper, sometimes harsher edge, and lime juice adds both acidity and a hint of bitterness. Orange juice brings sweetness and moderate acidity, which is often useful in sauces and baking where a subtle touch is required.

For creamy dishes, yogurt or sour cream smoothly blend acidity with richness. Parmesan cheese not only adds acidity but also umami and saltiness, altering the dish’s flavor profile. Consider whether a strong or subtle acid is more appropriate for the recipe’s outcome.

When deciding, it helps to match both the acidity and the flavor profile of the original ingredient. Testing and adjusting the quantity may also be necessary, as some substitutes (such as vinegar) can quickly overpower a dish.

Adjusting for Cooking Methods

Different cooking methods impact how acid behaves in a recipe. Baking often relies on acid to activate leavening agents like baking soda, so using a substitute with similar acidity is important for proper texture. In these cases, buttermilk, yogurt, or lemon juice usually work well.

For uncooked applications, such as salad dressings or marinades, flavor intensity matters more. Here, the distinct taste of the substitute may become more pronounced. Vinegar and lemon juice can be swapped, though amounts may need adjusting to avoid overpowering other flavors.

When reducing acidity in cooked sauces, a milder substitute such as orange juice or even a splash of broth can soften sharpness. Always add acidic ingredients gradually and taste frequently, as heat can intensify or mellow their effects during cooking.

Substituting Alkaline Ingredients in Recipes

Alkaline ingredients impact not just leavening, but also color, flavor, and texture in both sweet and savory recipes. Finding suitable substitutes requires understanding the chemical effects each ingredient brings to the dish.

Best Alkaline Substitutes: Baking Soda and More

Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) is the most common alkaline ingredient used for leavening and browning. When there is no baking soda available, several swaps are possible:

Baking Powder: Use 3–4 times as much baking powder to replace baking soda, since it contains acids and is less potent.

Potassium Bicarbonate: Provides similar leavening without sodium, useful for low-sodium diets.

Baker's Ammonia (Ammonium Carbonate): Mostly suited for crisp cookies and crackers.

Cream of tartar is sometimes used with baking soda to neutralize acidity and achieve a more alkaline environment, especially in meringues.

For yeasted recipes like pretzels, baking soda is often used in the boiling process to create the classic brown, chewy crust. If substituting, a combination of baking powder and a small amount of cream of tartar may mimic some of that alkalinity, but sodium bicarbonate remains the gold standard.

Considerations for Texture and Taste

Substituting alkaline ingredients can change both mouthfeel and taste. For example, cocoa powder comes in two forms—natural and Dutch-processed. Dutch-processed cocoa is alkalized, which means if a recipe calls for it, using natural cocoa instead may require adjusting the amount of baking soda or powder.

Alkalinity can soften structures in baked goods. Too little can result in dense textures, while too much may create soapy off-flavors or yellow tinges. Some recipes, such as those for chewy pretzels or specific cookies, rely on alkaline solutions for their signature color and tang.

When making substitutions, check if the recipe includes acidic ingredients like buttermilk or yogurt. You may need to balance the swap by reducing or increasing acids to keep the pH right. Using a table like the one below can help:

Original Ingredient Substitute Notes 1 tsp baking soda 3–4 tsp baking powder May alter flavor slightly Dutch cocoa Natural cocoa + baking soda Adjust for acidity Baking soda (pretzels) Baking powder + cream of tartar Texture may differ

Attention to detail ensures substitutes function correctly without negatively impacting texture, rise, or browning.

Substituting Dairy and Dairy Alternatives for pH Balance

Dairy and non-dairy ingredients influence a recipe’s final pH and overall taste. Understanding their effects on acidity or alkalinity in complex recipes allows for better control over flavor and health considerations.

Dairy Substitutions: Milk, Cream, and Yogurt

Standard cow’s milk has a slightly acidic pH, typically around 6.5 to 6.7. In recipes, this slight acidity can impact the consistency of baked goods and the reaction with leavening agents.

Heavy cream and evaporated milk are commonly used when a richer, less acidic component is needed. Cottage cheese and ricotta cheese each bring mild acidity along with added texture. When swapping milk, using evaporated milk or cream can provide a smoother, less tangy result due to their lower acid profile.

Plain yogurt introduces more acidity compared to milk, which can tenderize batters or dough. For sauces and dressings, combining cottage cheese or mayonnaise may achieve creaminess without increasing acidity as much as yogurt would. The following table shows typical pH values:

Ingredient Typical pH Range Cow’s Milk 6.5 – 6.7 Heavy Cream 6.5 – 6.8 Yogurt 4.0 – 4.5 Cottage Cheese 4.5 – 5.2

Non-Dairy Options for Acidity and Alkalinity

Non-dairy milks such as coconut milk and soy milk offer less acidity than dairy yogurt and are often used to maintain a more neutral or slightly alkaline pH in recipes. Coconut milk, in particular, is nearly neutral to slightly alkaline, and it adds creaminess to dishes.

Soy milk is close to neutral, making it suitable for those seeking to avoid increasing a dish’s acidity. In savory recipes, using soy sauce can raise acidity, but pairing it with alkaline ingredients like certain plant-based milks or baking soda may balance pH.

Ricotta alternatives made from nuts or tofu tend to be mild in acidity. Selecting almond milk or oat milk can be a practical swap for those wanting to minimize recipe acidity. Adjusting the amount and type of non-dairy substitute can ensure baked goods rise properly and sauces remain stable.

Sweeteners and Their Effects on Acidity and Alkalinity

Sweeteners influence both flavor and the chemical environment of a recipe. Their impact on acidity or alkalinity can change texture, taste, and even color.

Sugar, Honey, and Syrup Variations

Granulated sugar is neutral in pH, so it does not make a recipe more acidic or alkaline. Brown sugar contains molasses, which is slightly acidic and adds moisture and mild acidity to baked goods. Powdered sugar, usually mixed with a small amount of cornstarch, is also near neutral but can slightly affect the texture.

Honey and maple syrup are naturally acidic. Honey’s pH ranges from about 3.4 to 6.1, while maple syrup is around 5.5 to 7. This acidity can react with alkaline baking ingredients, such as baking soda, to create a tender crumb or cause leavening. Molasses, used to make brown sugar, is notably acidic, affecting both pH and flavor profiles. Corn syrup is less acidic, tending closer to neutral.

Chocolate and cocoa powder vary: natural cocoa is acidic, while Dutch-processed cocoa is alkalized and more neutral. When combined with sweeteners, these can significantly alter the overall pH of a recipe.

Baking with Sweetener Substitutes

Artificial or alternative sweeteners, such as stevia, tend to be more neutral or even slightly alkalizing compared to traditional sweeteners. For example, stevia has been shown to have mild alkalizing properties, balancing out acidity in some recipes. Unlike sugar or honey, these substitutes may not react with baking soda or powder in the same way, potentially affecting rise and texture.

When substituting sweeteners, consider not only sweetness but also chemical reactivity. Some, like erythritol or xylitol, are almost pH-neutral and do not facilitate browning or leavening as efficiently as sugar. Syrups made from agave or rice may introduce mild acidity but less than traditional honey or molasses.

Below is a table summarizing the general pH tendencies and common effects of popular sweeteners:

Sweetener Typical pH Effect on Recipe Acidity Granulated Sugar ~7 (neutral) Minimal Brown Sugar ~5.5-6 (slightly acidic) Adds mild acidity Powdered Sugar ~7 (neutral) Minimal Honey 3.4–6.1 (acidic) Increases acidity Maple Syrup 5.5–7 (mildly acidic to neutral) Mild acidity Molasses 5–7 (acidic) Pronounced acidity Corn Syrup ~7 (neutral) Minimal Stevia ~7+ (alkaline) May reduce acidity

Choosing the right sweetener is essential for both taste and proper chemical reactions during baking.

Substituting for Acidity and Alkalinity in Baking

The balance between acidity and alkalinity affects how leavening agents work and can also influence the structure, texture, and flavor of baked goods. Correct substitution helps maintain the expected rise and mouthfeel, even when ingredients must be replaced.

Adapting Leavening Agents for Balanced pH

Baking recipes often rely on a specific pH level for optimal results. Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) requires an acid—like buttermilk, yogurt, or lemon juice—to activate and release carbon dioxide, which makes baked goods rise. If no acid is present with baking soda, products may turn out dense and soapy-tasting.

When substituting, baking powder can stand in for baking soda because it contains both acid and alkali. However, it’s less potent, so recipes typically need three times more baking powder than baking soda. The following table outlines common leavening substitutions:

If Recipe Calls For Use Instead Ratio Baking soda Baking powder 1:3 (1 tsp : 3 tsp) Acid + Baking soda Baking powder only Omit acid, triple powder

Flours and other starches usually do not affect pH much, but using whole wheat or alternative flours may introduce additional acidity, which sometimes calls for extra alkali.

Swapping Ingredients to Achieve Desired Texture

Ingredients like milk, yogurt, sour cream, and buttermilk all have different acidities. Swapping one for another impacts texture and crumb. Substituting regular milk (pH ~6.5) with buttermilk or yogurt (lower pH) makes batters more acidic. In these cases, reduce the acid in the recipe or add a bit more baking soda to balance it out.

Fats such as butter and eggs influence structure and moisture. Butter is neutral, but certain recipes using acidic dairy demand adjustment of leavening agents when swapping in less acidic alternatives. For eggs, the proteins coagulate at different rates depending on pH, impacting rise and texture.

Adjustments must take ingredient acidity, starch composition, and fat content into account. For example, using sweet cream butter in place of cultured butter changes acidity slightly, often without a major effect, but switching from whole eggs to only egg whites can make the mixture less fatty and more alkaline. This may require increasing starch or reducing baking soda amounts to keep texture.

Enhancing Flavor and Adjusting Taste in Complex Dishes

Complex dishes often require precise management of both flavor balance and ingredient interactions. Flavor can be adjusted by layering specific seasonings or by selectively reducing acidity, depending on the needs of the recipe.

Using Herbs, Spices, and Aromatics

Herbs and spices provide depth while allowing for fine-tuned adjustments. Fresh parsley, mint, and allspice each deliver distinct layers to otherwise flat profiles. Aromatics like onion, garlic, and ginger introduce a sharpness and aroma that can mask minor imperfections or enhance savory notes.

For further enhancement, sautéed mushrooms contribute umami and earthy undertones, working particularly well in sauces and stews. Onion powder is useful for even distribution in liquid-based recipes. Table: Common Flavor Enhancers

Ingredient Main Contribution Garlic Savory, pungent Onion/Onion Powder Sweet, aromatic Ginger Spicy, zesty Mint Fresh, cooling Parsley Bright, herbal Allspice Warm, sweet-spicy Sautéed mushrooms Earthy, umami

Strategic use of these ingredients helps maintain complexity without overpowering primary flavors.

Correcting Overly Acidic Dishes

When a dish becomes too acidic, the quickest fixes involve balancing acids with complementary flavors. Adding a small amount of sweetener (such as sugar or honey) can reduce sharpness without shifting the dish away from its original intent.

Cream or butter can round off harsh acidity in sauces, while sautéed mushrooms and other umami-rich foods buffer acidity for a smoother finish. Including herbs like parsley or mint lightens aftertaste and freshens perception.

In soups and stews, adding potatoes or a small amount of starch absorbs some acidity. Salt, used sparingly, can mask sourness but should not be the only adjustment. For highly acidic tomato-based dishes, simmering with aromatics (onion, garlic) mellows the overall tone.

Cooking Techniques and Their Impact on Acidity and Alkalinity

How food is cooked changes its pH, influencing both flavor and texture. Methods such as roasting, steaming, and sautéing can raise or lower acidity or alkalinity, affecting the overall balance of a dish.

Roasting, Steaming, and Sautéing

Roasting tends to concentrate flavors and reduce moisture. As water evaporates, acids become more noticeable, and browning (via the Maillard reaction) can lower the perceived acidity, yielding a milder, sweeter taste.

Steaming uses water vapor and has little effect on acidity, as it cooks food gently and does not promote browning. The pH of the final dish stays close to the ingredient’s initial level.

Sautéing, which often employs olive oil or vegetable oil, can quickly soften acidic vegetables and mellow their sharpness. The choice of oil and cooking time may influence the final taste but will not drastically alter the food’s natural pH.

Modifying Recipes for Balanced pH

Appling acids or bases can fine-tune a recipe’s balance. For overly acidic dishes, cooks may add small amounts of alkaline ingredients like baking soda. This neutralizes excess acid and softens sharp flavors.

Conversely, a squeeze of citrus or a splash of vinegar increases acidity in a dish, brightening flavors and helping emulsify dressings. Adjusting cooking methods, such as using less liquid when roasting, further helps concentrate or balance pH.

Monitoring technique and ingredient choices is key when adapting a recipe for desired acidity or alkalinity. Tasting and adjusting step-by-step ensures the final result meets both texture and flavor goals.

Less Common Substitutions and Creative Solutions

Certain ingredients add unique flavors or chemical properties to recipes but are not always on hand. Understanding how to substitute for these less common items can help preserve recipe balance, especially when managing acidity and alkalinity.

Alcohol and Fermented Ingredients

Alcohols such as beer, rum, or brandy are sometimes used for flavor, tenderizing, or as part of the leavening process in baked goods and savory dishes. When a recipe calls for alcohol, substitutes should offer similar acidity or effect on texture.

For beer in batters or breads, try using club soda or a mixture of water and a splash of vinegar for lightness. When replacing rum or brandy, use an equal volume of apple juice, white grape juice, or a blend of juice and a teaspoon of vinegar to mimic both the moisture and acidity. Fermented ingredients such as raisin puree or yogurt can also introduce mild acidity and complex flavors.

A table can clarify these options:

Ingredient Substitute Notes Beer Club soda + vinegar Maintains lift; subtle tang Rum/Brandy Apple juice + vinegar Similar sweetness and acidity Fermented Yogurt, raisin puree Adds tang; may adjust texture and flavor

Hydroxide ions introduced by alcoholic or fermented ingredients impact both taste and pH, so it's important to maintain that balance when substituting.

Specialty Fats and Plant-Based Options

Lard and margarine influence moisture, richness, and mouthfeel. For those looking to avoid animal fats, plant-based options can be effective, but ratios and structural changes must be considered.

Vegetable shortening or coconut oil can substitute for lard in pie crusts and pastries. For margarine, use equal amounts of plant-based butters or mixture of olive oil and a bit of coconut oil for improved texture and a neutral flavor.

Ingredient substitutions for specialty fats can alter leavening when they interact with baking soda (a source of hydroxide ions). The water content in margarine, for instance, can require an adjustment in dry ingredients. For even more creativity, nut butters or mashed avocado offer richness, though they may add flavor notes and tint.

List of plant-based substitutions:

Lard: Vegetable shortening, coconut oil, mashed avocado

Margarine: Plant-based butter, olive oil with a touch of coconut oil

Maintaining structural integrity, especially in delicate pastries, often means chilling plant-based fats and keeping quantities precise.